A Routine Cargo Run Turns Tragic

In the quiet pre-dawn hours of October 5, 2021, a Dassault Falcon 20 jet, operating as Pak West Airlines Flight 887 for Sierra West Airlines, lined up for an instrument approach into Thomson-McDuffie County Airport (HQU) in Georgia. It was a familiar night cargo run — but this flight would end in devastation. Less than a mile from the runway, the aircraft collided with trees and terrain, killing both the captain and first officer on board.

This is the story of how miscommunication, procedural deviations, and poor cockpit dynamics converged in the darkness, culminating in tragedy. As always, our goal here isn’t just to recount what happened, but to understand why — and how future accidents can be prevented.

The Crew: Experienced, but Strained

The captain, 73 years old, was an airline transport pilot with over 11,955 hours of total flight time, including 1,665 hours in the Falcon 20. Despite his experience, his training history revealed multiple checkride failures and retraining for tasks like steep turns and circling approaches.

The first officer, aged 63, held a commercial certificate with 10,908 hours total, and 1,248 hours in the Falcon 20. However, despite his years with the company, he had never been promoted to captain. The operator noted persistent concerns about his airmanship and decision-making.

Together, they were a seasoned pair. But experience alone wasn’t enough — and their cockpit chemistry would soon reveal deep cracks.

Setting the Stage: Delays and Darkness

The flight had two legs that night. The first, from El Paso to Lubbock, was uneventful. But once in Lubbock, a 2-hour, 20-minute freight delay pushed their schedule into the early morning hours. The second leg, destined for HQU, launched into darkness under a high-stress, fatiguing rhythm — not uncommon in the cargo world.

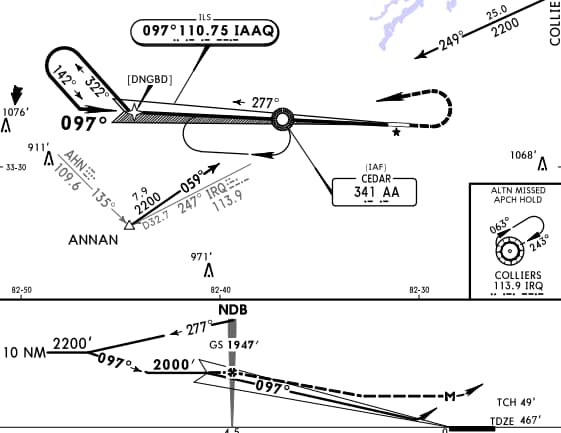

Approximately 40 minutes from Thomson, the crew queried air traffic control about NOTAMs affecting the airport’s ILS approach. The response was problematic: the controller incorrectly admitted he didn’t understand the abbreviation “GP” (glidepath) and didn’t inform the pilots that the glidepath was not in service — a crucial fact. Though not required to emphasize it, this lack of clarity created confusion at a critical moment.

A Fast and High Approach

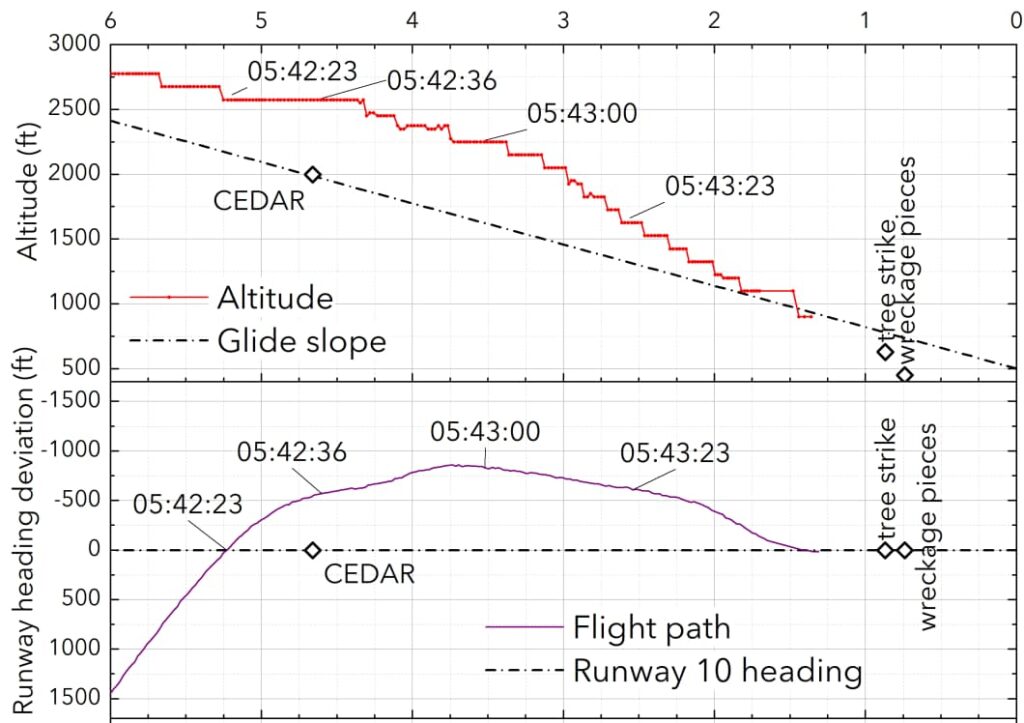

As the aircraft neared its destination, the captain reported the airport in sight and canceled IFR services. But the approach was already deteriorating.

They crossed the final approach fix high, fast, and off course. Airspeed was around 150 knots — well above the Vref of 113 knots. The aircraft was 600 feet above a standard 3° glide path, and trending left of the centerline.

Instead of calling for a go-around, the captain instructed the first officer to use the air brakes — a procedure explicitly prohibited by the aircraft flight manual unless anti-ice was in use (it wasn’t). The aircraft entered a high descent rate, with the air brakes deployed, landing gear extended, and flaps set to full. There’s no manufacturer data for this configuration — it’s simply not how the Falcon 20 was meant to fly on approach.

Cockpit Breakdown

The cockpit voice recorder paints a disturbing picture of a dysfunctional crew. The captain — who was not the flying pilot — repeatedly yelled at and criticized the first officer during descent. He gave conflicting and urgent instructions, took the controls multiple times, then handed them back.

“You fly the damn airplane,” he barked, frustrated and exhausted. “I don’t want you to kill me.”

This wasn’t just stress. It was a breakdown in crew resource management (CRM) — the collaborative communication and decision-making process that’s foundational to safe flight. At multiple points, the captain had opportunities to take over, especially given the first officer’s known performance issues. But instead, the flight continued down an unstable and dangerous path.

No stabilized approach callouts were made. No go-around was initiated.

At one point, the first officer denied being high, contradicting the captain. Moments later, the captain warned, “You got trees.” The engines spooled up, the stall warning sounded — and then silence.

The Crash

The Falcon 20 impacted trees approximately 0.7 nautical miles from the runway threshold. Surveillance footage confirmed that visibility wasn’t a factor — the aircraft’s landing lights were visible until the moment of impact. The aircraft broke apart over an 880-foot debris field. There was no fire. Both pilots died of blunt force trauma.

Investigators later confirmed that both air brakes were extended, and power was near flight idle until just seconds before impact. A last-ditch application of thrust came too late.

What Went Wrong: A Cascade of Failures

The NTSB identified the probable cause as the flight crew’s continuation of an unstable approach and use of air brakes in violation of aircraft limitations. But that’s only the beginning.

Several contributing factors included:

- CRM Failure: The captain’s decision not to take over despite obvious signs of trouble.

- Training Gaps: Both pilots had histories of subpar performance, yet were still flying together.

- Lack of SMS and FDM: The operator had no Safety Management System or Flight Data Monitoring — tools that might have flagged the crew’s repeated procedural deviations before disaster struck.

- ATC Communication Issues: While not deemed causal, the controller’s misunderstanding of NOTAM terminology added confusion.

Lessons in Leadership and Safety

This accident underscores a painful truth in aviation: even experienced pilots can make catastrophic mistakes, especially in a toxic or dysfunctional cockpit environment. Leadership in the air is about more than just seniority or hours logged — it’s about judgment, communication, and teamwork.

Some key takeaways:

- Stabilized approaches save lives. If you’re too high, too fast, or not configured properly — go around. Always.

- Crew Resource Management is vital. A flight deck must be a place of clarity and collaboration, not conflict and chaos.

- Proactive safety systems matter. SMS and FDM aren’t bureaucratic checkboxes; they’re vital tools to identify risks before they become accidents.

In Memory

This flight ended in tragedy, but it leaves behind vital insights for the industry. Safety is not just about the aircraft — it’s about the culture, the communication, and the decisions made under pressure. Let’s honor these lessons with action.