Valentine’s Day should have been a memorable evening for Allan and Calli, a pilot and his wife who set off on what seemed like a routine cargo flight. Instead, the trip ended in tragedy when their Cessna 210L (N732EJ) crashed just moments before landing in Birmingham, Alabama. The heartbreaking reality? This flight should never have happened.

The Pilot: Allan’s Background and Qualifications

Allan, 44 years old, was an experienced pilot but had a history of struggling with check rides. He obtained his private pilot certificate in 2007, and his instrument rating in 2008 (though he initially failed his check ride). Over the years, he built up his experience, eventually earning his commercial certificate and becoming a certified flight instructor (CFI). However, he failed both his initial CFI check ride and his multi-engine check ride before eventually passing.

By 2012, Allan was hired by Southern Seaplane, Inc. to fly cargo in a Cessna 210—a high-performance, six-seat aircraft with retractable landing gear. He completed an initial check ride for the company, but never finished the instrument proficiency portion, meaning he was only authorized for VFR (Visual Flight Rules) flights under Part 135.

In 2013, due to a drop in demand, Allan was put on inactive duty. He requalified in January 2014, but once again, his check ride paperwork stated “VFR Only”—which meant he was not authorized to fly IFR (Instrument Flight Rules) flights for the company.

Unfortunately, that restriction would be completely ignored on the night of the crash.

A Long Day Leading to Disaster

Allan had been on duty for nearly 16 hours before the accident. His day started early, and it wasn’t just an ordinary day—it included a checkride to obtain a seaplane rating, adding to the mental and physical workload.

Later in the day, he accepted a flight to transport blood specimens for the Mississippi Organ Recovery Agency (MORA). The plan was to fly from Stennis International Airport (HSA) in Mississippi to Birmingham (BHM) and then to Jackson (JAN), but bad weather forced him to alter his route.

As delays stacked up, his duty time grew longer and longer. By the time he finally departed Jackson, he had been awake for at least 16 hours, and his fatigue was likely severe. Fatigue is often compared to alcohol intoxication in terms of its effects on cognitive function, reaction time, and situational awareness. Studies have shown that being awake for 17 hours can impair performance as much as a blood alcohol level of 0.05%—and for 20+ hours, the effects mimic being legally drunk.

At 21:06, Allan departed Jackson, Mississippi, bound for Birmingham under visual flight rules (VFR). The weather forecast for Birmingham predicted a 1,500-foot ceiling and 6 miles of visibility, but upon arrival, the airport was operating under instrument flight rules (IFR) due to deteriorating conditions.

Despite being instrument-rated, Allan was only authorized to fly VFR for revenue operations under Part 135. More concerning, he was not current for night flight, something his employer failed to check before dispatching him.

Upon contacting Birmingham Approach at 22:08, Allan requested an IFR clearance for an Instrument Landing System (ILS) approach to Runway 24. The controller confirmed that he was capable and qualified for IFR flight, to which he incorrectly responded “affirmative”. At this point, Allan had already made a critical decision error—continuing into IMC despite not being legally qualified for it.

The Crash: Spatial Disorientation, Fatigue, and a Deadly Turn

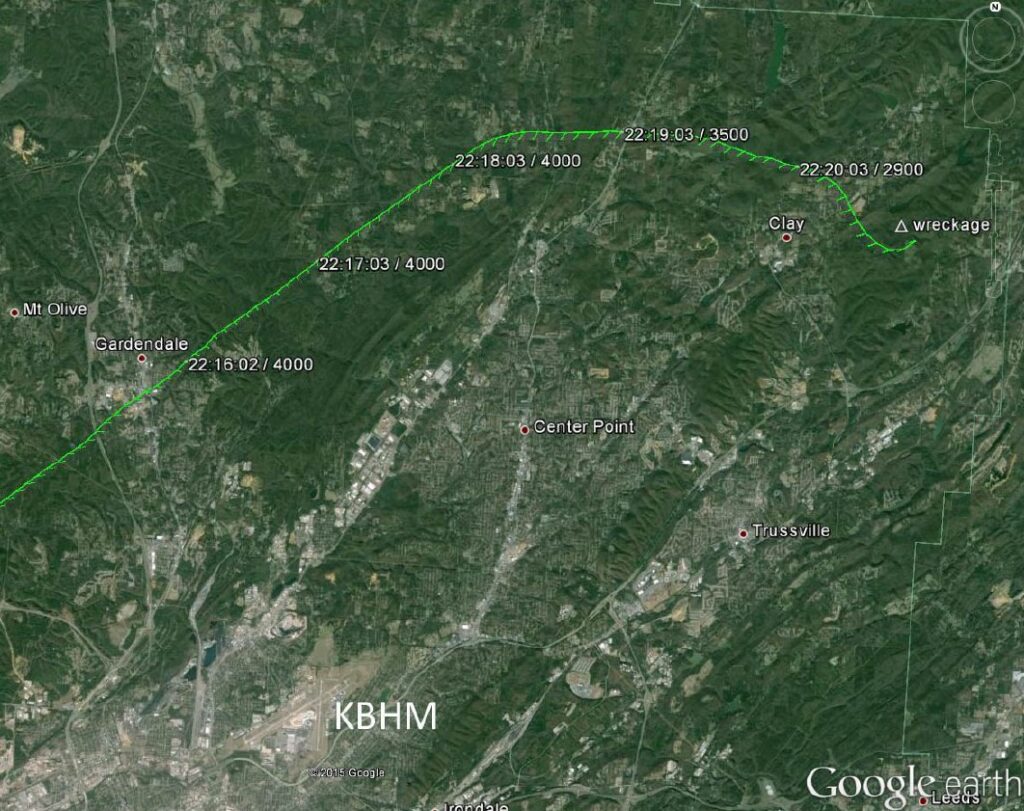

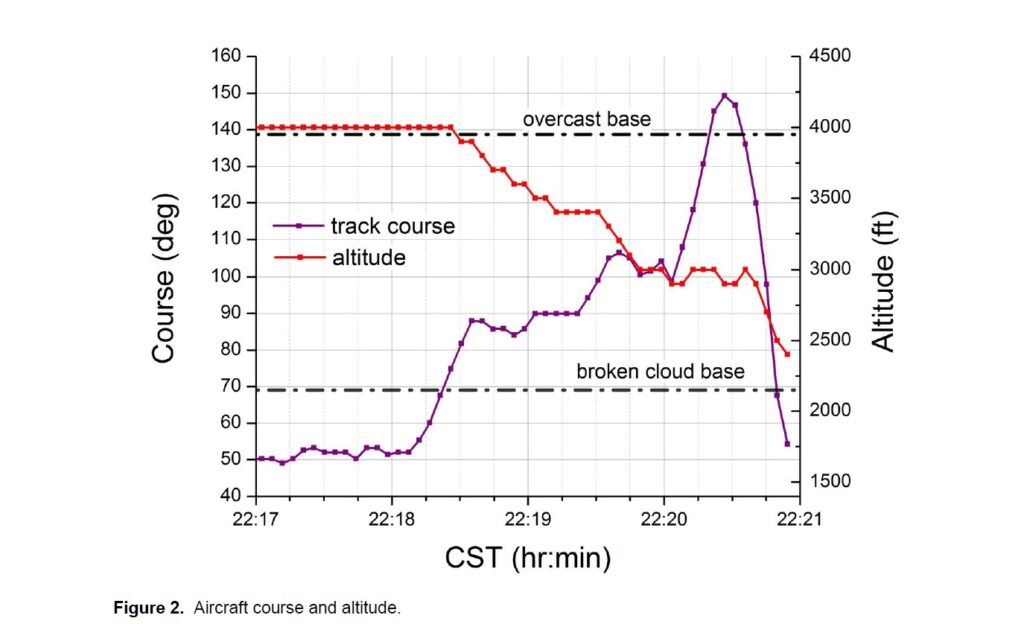

As the aircraft was vectored to intercept the localizer, things went horribly wrong. Instead of turning right as instructed, the plane made a steep left turn, entering a bank three times steeper than a standard turn. Radar data showed a left bank angle reaching 60 degrees—a turn rate that is extremely dangerous in IMC.

Just two seconds after his final radar return, the pilot transmitted, “Say again for Two Echo Juliet.” This suggests he was either confused, disoriented, or struggling to keep up with cockpit duties. The controller quickly instructed him to level the wings and climb, but there was no response.

The aircraft crashed into trees and terrain less than a mile from the last radar hit, with no signs of pre-impact mechanical failure.

The Operator’s Failure: Inadequate Dispatch Procedures

While the pilot bears primary responsibility, Southern Seaplane, Inc. also played a significant role in this accident.

- They dispatched a pilot who was NOT night-current.

- Their records did not adequately track night currency.

- They allowed the pilot to fly beyond his duty limits.

- While legal at the start, delays extended his duty time far beyond safe limits.

- They did not verify the weather and take into consideration that Allan was only approved for VFR flights.

- They did not enforce their own call-in procedures.

- The pilot was supposed to call in after landing to discuss the weather before continuing. He did not, and no one followed up.

If the company had proper tracking and enforcement mechanisms, this accident might have been prevented.

Key Safety Lessons from this Tragedy

1. Fatigue is a Killer—Respect Duty Limits

Pilots and operators must treat fatigue like any other impairment. If a pilot has been on duty for too long, they should not fly—period. The human brain is simply not designed to function well after 16+ hours of wakefulness.

2. If You’re Not Current, Don’t Fly

Currency requirements exist for a reason. If you haven’t flown at night or in IMC recently, you cannot be expected to perform well under stress.

3. Follow Proper Dispatch Procedures

The operator should have checked the pilot’s night currency and duty time. Dispatch procedures should include strict enforcement of these limits.

4. Never Be Afraid to Divert or Delay a Flight

The safest option is often to wait. The pilot felt pressure to continue due to his delays, but a safe outcome is always more important than being on time.

Final Thoughts

This was a heartbreaking accident that left four children without their parents. It’s especially tragic because it was entirely preventable. The best way to honor Allan and Calli’s memory is to learn from their mistakes—so that no other pilot makes the same fatal errors.

3 Comments

all of the above makes clear sense … when I flew in Northern Ontario, I always brought an IFR instructor with me to do the radio work … that way, I could focus

on the flying and I am still here !

Unless the FAR has changed, it is against regulations for anyone to “fly along” on a commercial flight unless; 1) the aircraft is rated for two pilots; 2) there is cargo that requires specialized handling, like animals or HAZMAT.

I learned this from personal experience. Luckily, I didn’t get rung up for it.

Unless the FAR has changed, it is against regulations for anyone to “fly along” on a cargo flight unless; 1) the aircraft is rated for two pilots; or 2) there is cargo that requires specialized handling, like animals or HAZMAT.

I learned this from personal experience. Luckily, I didn’t get rung up for it.