On the morning of April 29, 2019, a Robinson R44 on a Part 135 sightseeing flight around Oahu entered clouds over Kailua, encountered rapidly changing weather, and broke up in flight. The helicopter, registration N808NV, impacted a residential street and was destroyed. The commercial pilot and two passengers did not survive. Investigators later concluded that a strong downdraft or outflow boundary, combined with higher-than-recommended airspeed in turbulence, led to a low-G condition, mast bumping, and main-rotor contact with the cabin that tore the aircraft apart in flight.

The Pilot, the Helicopter, and the Mission

The pilot was 28 years old, a working professional aviator. He held a commercial pilot certificate with rotorcraft-helicopter and instrument helicopter ratings, and he was also a helicopter and instrument helicopter flight instructor. At the time of the accident he had about 540 total flight hours, 470 hours as pilot in command, and roughly 340 hours in the Robinson R44—so most of his time was in the same make and model he was flying that day. In the prior 90 days he had logged 135 hours, and 6 hours in the last 24 hours, all in helicopters.

He had been hired by the operator about two and a half weeks earlier, completed the company’s Part 135 training on April 19, then a week of tour-specific training. He began carrying passengers on tours only about three days before the accident. This flight was his first sortie of the day, departing Daniel K. Inouye International Airport (HNL) for a standard island tour.

The helicopter itself was a 2000-model R44, a four-seat machine with a two-bladed, semirigid rotor system and Lycoming O-540 engine, operating under a commuter air carrier certificate.

Weather Building Over Windward Oahu

On paper, the nearest observation—about 3 NM away—still showed VMC: visibility around 4 miles, broken clouds at 1,800 feet, light rain, and moderate trade winds. But that snapshot did not tell the whole story.

The larger-scale picture had a surface trough draped over the northwestern Hawaiian Islands, feeding warm, moist air into mountainous terrain. That’s a recipe for showers and embedded convection. A model sounding for the area showed a conditionally unstable atmosphere from the surface up through about 12,500 feet, with potential outflow or downdraft winds at the surface up to roughly 37 knots. Weather radar showed light to moderate echoes along the route, and, more importantly, a descending core of 20–30 dBZ reflectivity moving down toward the surface above Kailua around the time of the accident.

In simple terms: it was a day where a pilot might see what looks like marginal-but-workable VFR, yet be just one shower or outflow boundary away from rapidly deteriorating visibility and unexpected vertical and horizontal gusts.

The Final Minutes of Flight N808NV

N808NV and another company helicopter departed HNL around 0854, tracking east along the south shore. They then turned northwest along the windward side. At 0907:58, the accident pilot checked in over Bellows Air Force Base and requested a northwest transition, which ATC approved. A second company helicopter, a short distance behind, made the same request.

About a minute later, the controller asked both helicopters, “How is the weather looking over Kailua right now?” The trailing helicopter, farther offshore, replied that conditions were “still VFR, but it’s getting a little bit harder to see,” and turned toward the water to stay in better visibility. About 10 seconds later, the accident pilot—who was further inland and closer to the developing weather—asked to alter his course similarly, and was told to maintain at or above 600 feet.

The accident helicopter initiated a right turn toward the water at a groundspeed of about 108 knots. That’s a normal R44 tour speed in smooth air, but above the 60–70-knot range Robinson recommends in significant turbulence. The helicopter continued toward the water for about half a nautical mile, then began a left turn back inland over Kailua, with speed sliding from 108 to about 104 knots.

As the helicopter paralleled a roadway, groundspeed continued to bleed down to about 92 knots. At roughly 0.19 miles from the eventual impact point, the helicopter was about 1,700 feet above ground level. Then the track shows an abrupt descent. The final radar return, only 0.11 miles from the site, put the helicopter at about 1,425 feet AGL, coming down at roughly 7,360 feet per minute. Shortly after, radar coverage ended.

Witnesses on the ground later described hearing the helicopter overhead but not seeing it because of low clouds and heavy precipitation. They reported very loud rotor noise, then a sharp metallic bang and the sound of tearing metal. One witness saw a piece of rotor blade emerge from the clouds and spiral down. Another saw the helicopter itself pitch forward, roll, and fall nose-low with no apparent rotor rotation, as if it had simply stopped flying and entered a freefall.

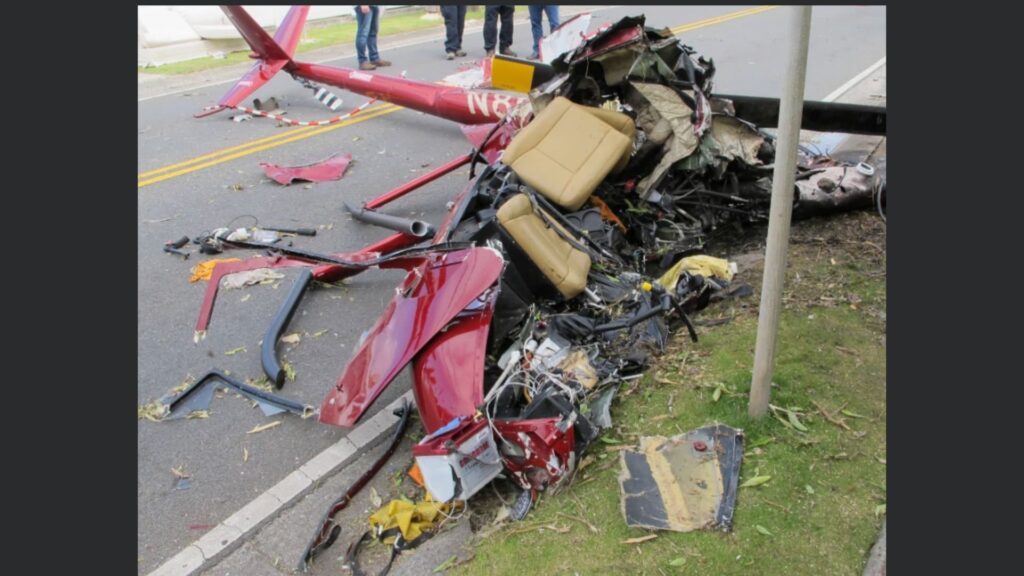

What the Wreckage Told Investigators

The wreckage trail stretched about a quarter mile through a residential area on a roughly north-south track. The outboard third of one main rotor blade was found early in the debris path, stuck in a fence. Scattered left-side airframe and cabin components followed, along with the separated main fuel tank. The main fuselage came to rest on its left side in the street, heavily damaged and burned.

The left forward cabin and roof area showed clear signs of being struck by a main rotor blade—exactly the kind of evidence you look for in a mast-bumping or excessive flapping event. The corner of the instrument console was crushed inward toward the passenger space. The left cabin seats were crushed from outboard to inboard.

At the rotor system, investigators found the main rotor driveshaft bent roughly 20 degrees above the swashplate, with arc-shaped scoring on both sides of the rotor hub near the pitch horns. Both teeter stops were crushed, and the droop-stop bolt was sheared at the nut, though still in place. On the red main rotor blade, a 45-inch spanwise dent on the lower surface carried evenly spaced marks that matched the line of screws in the windshield bow—essentially a fingerprint of the blade hitting the cabin structure.

By contrast, the tail rotor system was largely intact, with only minor non-rotational impact damage. The engine teardown showed no mechanical issues; all evidence suggested it was producing power at impact. The breakup did not start with a power loss—it started at the rotor system.

Understanding Low-G, Mast Bumping, and the R44

The R44 uses a two-bladed semirigid, teetering rotor system. In normal, positive-G flight, it’s a simple and robust design. But like any teetering rotor, it is vulnerable to certain combinations of low-G and aggressive control inputs.

In a low-G condition—like the top of a strong downdraft or sudden loss of lift—the fuselage can “unload” while the rotor disc is still moving through the air. If the pilot responds with abrupt lateral cyclic to counter a roll, rather than first gently reloading the disc with aft cyclic, the result can be excessive flapping. When flapping is great enough, the rotor hub’s static stop can strike the mast: mast bumping. From there, the sequence can be very fast—rotor blades can strike the tail boom, skid gear, or cabin, with catastrophic consequences.

Robinson’s Safety Notice SN-32, “High Winds or Turbulence,” specifically tells pilots to slow to 60–70 knots in significant turbulence, accept temporary deviations in altitude, airspeed, and heading, and use gentle, coordinated inputs to avoid overcontrolling. It’s guidance written with exactly this kind of environment in mind: convective outflow, gust fronts, and windward-side terrain.

In this case, the NTSB concluded that N808NV likely encountered a strong downdraft or outflow boundary while operating at speeds above the manufacturer’s recommended turbulence speed, resulting in a low-G condition, excessive main-rotor flapping, and in-flight breakup when the main rotor contacted the cabin.

Human Factors and Operational Context

From a pilot’s perspective, this accident sat at the intersection of several pressures and perceptions that are common in air tour flying.

The pilot was relatively new to the company and had only a few days of line tour experience, but he was not a brand-new helicopter pilot and had several hundred hours in type. That can be a tricky place to be: comfortable enough with the aircraft to feel at home, but still learning the operator’s routes, the local microclimates, and how quickly “Hawaii VFR” can slide into “no-go” on the windward side.

He was also in loose formation with another company helicopter. The trailing aircraft chose to turn out toward the water earlier and stayed VFR. N808NV was further inland, closer to the developing cells. Once you’ve committed to that inland track and cloud bases lower up ahead, the exit options start to narrow. It’s easy, in hindsight, to say “just turn around sooner” or “slow way down,” but in real time the pilot was juggling ATC instructions, passenger expectations on a scenic tour, and evolving weather that still looked technically VFR until it suddenly was not.

None of that excuses the outcome, but it explains the context—and that’s where the lessons live.

Key Safety Takeaways for Helicopter Pilots

A few points jump out of this report that are worth carrying into every rotorcraft flight review and preflight brief:

- Treat semirigid rotor systems with deep respect in turbulence. Know your helicopter’s recommended turbulence penetration speed and stick to it. In the R44, that means slowing to 60–70 knots any time you’re dealing with strong gusts, convective showers, or mountainous terrain mixing it all up.

- Review and practice (in the simulator or with an instructor) the correct low-G recovery technique: gentle aft cyclic to reload the disc first, then coordinated lateral cyclic as needed. Avoid abrupt lateral inputs in low-G.

- Don’t let “still technically VFR” be the bar in a tour environment. If visibility is trending down and cloud decks are lowering ahead—especially near terrain—turn around, change altitude, or pick a different route while you still have lots of maneuvering room.

- Remember that another aircraft on a similar route can see very different conditions just a mile or two away. The fact that one tour ship made it around doesn’t guarantee that your track, altitude, and timing will thread the same needle.

- As operators, make sure new line pilots get explicit local-weather mentoring: where the traps are, what radar products to watch, what “looks okay” but historically bites people.

N808NV’s breakup over Kailua was not caused by a mysterious mechanical failure. It was a combination of weather, airspeed, rotor-system limits, and human decision-making in a dynamic environment. The best way to honor the people who were lost is to absorb those lessons and make different choices the next time we find ourselves looking at a building rain shower over rising terrain, with the air starting to bump and the groundspeed still in the triple digits.