On October 17, 2022, an experimental, amateur-built Peryera Aventura II, registration N32856, launched from North Perry Airport (HWO) in the Miramar/Hollywood, Florida area for what was intended to be a straightforward Part 91 test flight. The goal wasn’t sightseeing or transportation—it was troubleshooting. In the days leading up to the accident, the airplane had been dealing with engine issues, including a reported intermittent in-flight power loss. The pilot and passenger were both employees of the airplane manufacturer, and they were actively chasing a problem that had already shown itself in the air. The flight ended just minutes after takeoff, when the airplane crashed into a residential area about a mile south of the departure airport. Both occupants were fatally injured. The NTSB determined the accident was caused by a total loss of engine power tied to a configuration that should have been changed per an engine manufacturer service bulletin.

The Pilot and the People Involved

The pilot was a 33-year-old commercial pilot and flight instructor with instrument privileges. He had about 1,700 total hours, but only about 10 hours in the Aventura II make and model. He was also flying a lot recently—about 500 hours in the prior 90 days—which suggested he was an active, working pilot. The passenger, 32, had no listed pilot certificate and no flight time. Both were restrained with 4-point harnesses. Toxicology on the pilot was negative for ethanol and drugs of abuse. In other words: no impairment story here, just a system that didn’t deliver power when it mattered most.

Setting the Stage: A Known Problem Airplane

One of the key threads in this event was that the engine issue wasn’t a surprise that popped up out of nowhere. A witness at the airport said the pilot and passenger stopped by to borrow a screwdriver on the day of the accident, and that the airplane had experienced problems in the days prior. That same witness also noticed that the engine “did not sound right” before departure. That’s not a diagnosis, but it’s an important clue: people nearby were hearing something abnormal before the airplane even left the ground.

The passenger had reportedly contacted a representative of the airplane manufacturer several days earlier and described an engine control unit (ECU) malfunction during flight that produced a power loss—then the engine came back and the airplane landed safely. That incident was passed to the engine manufacturer, and troubleshooting started. The engine manufacturer confirmed the report and even received a video showing the engine shutting down and restarting in flight. They suggested checks and noted the airplane required updates. The take-home point is simple: the system had already demonstrated a failure mode that could take the engine offline, and the team launched anyway to gather more information. That’s not inherently wrong—test flights exist for a reason—but it demanded disciplined risk management, strict configuration control, and a hard look at what “acceptable for flight” really meant.

The Flight: Normal Pattern Work Until It Wasn’t

At 11:35, the pilot called ground and received taxi instructions to runway 10R with a right-traffic departure. At 11:38, tower instructed the pilot to extend the downwind, and the pilot acknowledged. After that, the frequency went quiet from N32856.

At 11:39, tower advised that the airplane’s transponder wasn’t working, and then requested radio checks at 11:40 and 11:41 with no response. The NTSB report didn’t describe a drawn-out emergency call or a long troubleshooting session on the radio. There was just… nothing. A quiet cockpit and a quiet frequency often meant the crew was extremely busy, extremely behind the airplane, or both.

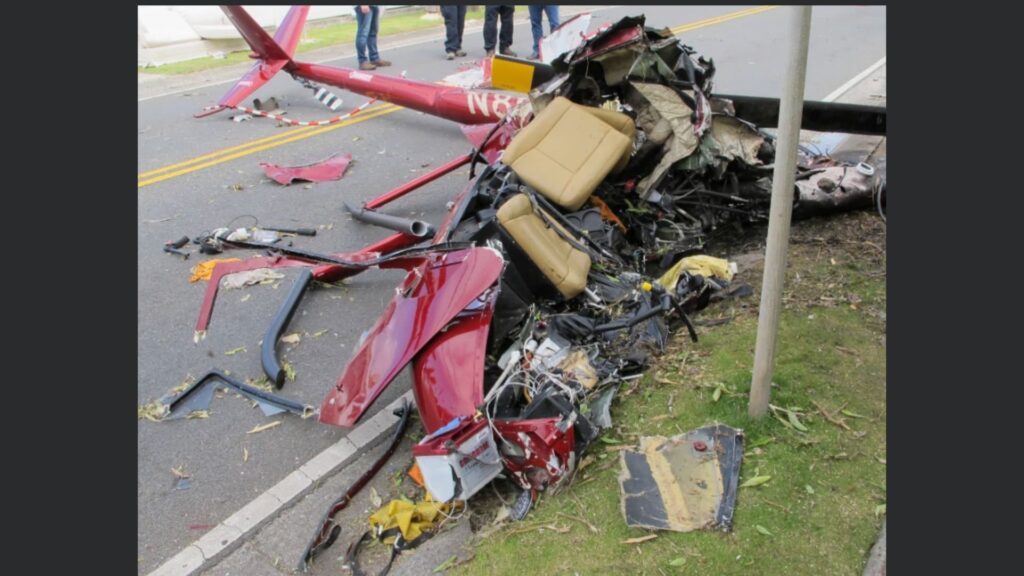

The crash site ended up in a residential area roughly one mile south of the airport, with the wreckage coming to rest partially on the roof of a residence. There was no post-crash fire. Weather was not a factor: it was daytime VMC with clear skies and good visibility.

Wreckage Clues: Fuel Onboard, Controls Connected, Engine Still Mounted

Investigators found all major components at the main wreckage site, and flight control continuity was confirmed to the primary control surfaces. The wings were impact damaged but partially attached. The engine remained attached to its mounts and showed no signs of impact damage. There was about a half tank of fuel onboard, and investigators didn’t find breaches in the fuel lines or tank.

That combination matters because it helped narrow the story. This didn’t look like fuel exhaustion, and it didn’t look like a pre-impact breakup. The evidence supported a scenario where the airplane was intact, controllable, and still had fuel—right up until it didn’t have usable engine power.

Investigators noted wiring connections were loose, consistent with being pulled during the accident sequence, and the battery terminal wires were also loose and stretched. Importantly, the operator had previously communicated that the passenger planned to inspect wiring connections before the flight. That’s another sign the crew knew the electrical/engine-control side of the house was in play.

The Smoking Gun: The ECU Select Switch and a Missed Service Bulletin

Here’s where the technical story tightened up. A post-accident engine test run was performed to replicate the reported power loss. The engine initially started and ran normally, but after several minutes it sustained a power loss. That’s a big deal because it suggested the failure wasn’t just “impact damage did it.” The engine could be made to misbehave under controlled conditions.

Further inspection showed the ECU wiring wasn’t in compliance with the engine manufacturer’s Service Bulletin for a Viking 110 wiring upgrade. The bulletin recommended removing the “computer on” selector switch—also referred to in the report as an “ECU select switch”—so the engine would operate on a single ECU. The service bulletin described removing wires labeled ECU 1, ECU 2, and SELECT, taping off ECU 2, and soldering ECU 1 and SELECT together with shrink tubing protection.

During functional testing, the power loss was consistent with malfunction of that switch. After the switch was removed, the engine operated normally. That’s the heart of the probable cause: the pilot’s failure to remove the ECU select switch per the manufacturer’s service bulletin led to a total loss of engine power.

If you’ve spent time around engine control electronics, this part should feel familiar. Switches, connectors, and logic paths can create failure modes that are intermittent, maddening, and perfectly timed to ruin your day. What made this one especially unforgiving was that it showed up at low altitude, close to the airport, right when you need reliability the most.

What the Cameras Showed: A Pattern of Intermittent Power Loss

The airplane carried onboard cameras. One unit didn’t yield data, but another (a GoPro Hero7) provided helpful context. It recorded a flight on October 11, 2022—six days before the accident—where the airplane suffered a sudden loss of engine power on final approach while the throttle remained stationary. The throttle was briefly pulled to idle and then advanced again; as it moved forward, power returned, and the airplane landed on runway 10R without further incident.

That clip underscored the hazard: the engine didn’t just run rough. It quit, and then came back. Intermittent failures are dangerous because they tempt you into believing you can “manage” them—until the day you can’t.

The same camera also recorded a flight on the day of the accident that began around 11:28 and ran about 7 minutes and 50 seconds. The airplane was on final for runway 10R, and a red light near the engine information display flashed for the duration. The engine sounded normal and responded to throttle. After landing, the airplane stopped on a taxiway and the two occupants discussed something while pointing at the display. The audio didn’t capture their conversation clearly, and the displayed values weren’t readable, but the sequence painted a picture: they were looking at indications, talking it through, and then they went right back around for another departure. The camera ended at 11:35:43, just before the accident flight timeline picked up with taxi and takeoff.

Safety Takeaways: This Was a Configuration Control Accident

There were two big lessons that landed here.

First, service bulletins and configuration changes mattered—especially on experimental/amateur-built aircraft and non-traditional engine installations where the system architecture might be more customizable than certified aircraft. In this case, the NTSB connected the fatal loss of power to an ECU select switch that should have been removed per the engine manufacturer’s guidance. When the investigators recreated the failure and then eliminated it by removing the switch, the causal chain became hard to ignore.

Second, intermittent faults demanded a different mindset. The airplane had already demonstrated an in-flight shutdown and restart. That’s not a nuisance squawk—that’s a serious reliability event. When you’re troubleshooting something that can shut the engine down, every subsequent flight needs to be approached like a disciplined test program: defined objectives, planned abort gates, conservative altitudes, and a bias toward “no-go” unless the configuration is known-good.

This accident also highlighted the trap of familiarity. The pilot was an experienced aviator overall, but he had minimal time in this specific make and model. Add a test-flight environment, active troubleshooting, and an intermittent engine control problem, and you’ve got the kind of workload stack that doesn’t leave much margin when something fails close to the ground.

Closing Thoughts

N32856 departed into good weather from a familiar airport on what was supposed to be a problem-solving flight. The crew wasn’t ignoring an unknown risk—they were chasing a known one. But the investigation showed the system still contained a switch and wiring arrangement that the engine manufacturer had specifically called out for removal. When the failure happened after takeoff, there wasn’t enough altitude, time, or margin to recover.

The story ended the way too many “we’re just going to take it up and see” troubleshooting flights ended: with an airplane that stopped producing power, and a crew that ran out of options before they could get it safely back on the ground.