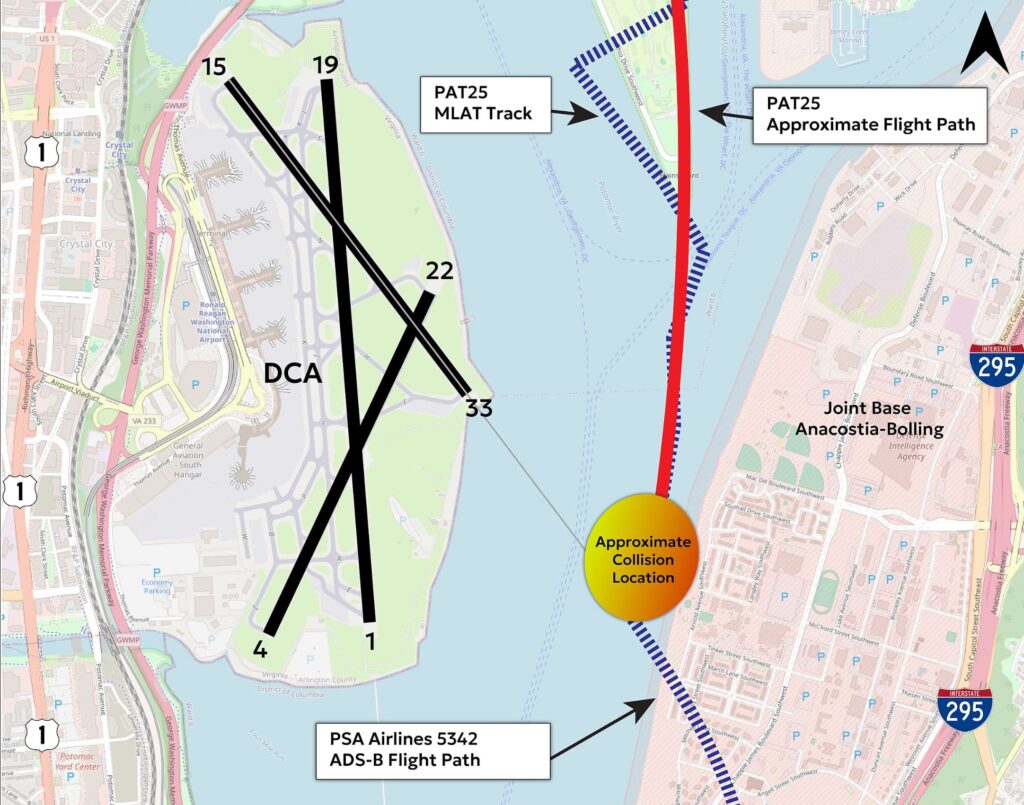

On the evening of January 29, 2025, a tragic midair collision occurred over the Potomac River near Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport (DCA). The accident involved a PSA Airlines Bombardier CRJ700, operating as American Airlines Flight 5342, and a U.S. Army Sikorsky UH-60 Blackhawk helicopter, operating as callsign PAT 25.

THE PLAN

American Airlines Flight 5342 (N709PS) was en route from Wichita, Kansas, to Washington, D.C., carrying 60 passenger and 4 crewmembers. The NTSB has not confirmed which pilot was flying the aircraft at the time of the crash.

U.S. Army Sikorsky UH-60 Blackhawk was carrying three crewmembers and was conducting a combined an annual and night vision goggle (NVG) check ride for one of the pilots. Typically, the pilot being evaluated sits in the right seat while the instructor sits in the left seat. The instructor pilot handles the radio calls while the other pilot focuses on flying the aircraft.

In complex airspaces like Washington Reagan National Airport (DCA), air traffic controllers follow specific deconfliction procedures to ensure safe separation between aircraft. The deconfliction plan for the UH-60 Blackhawk (Pat 25) and the CRJ (Flight 5342) was based on altitude separation, route structure, and visual separation protocols.

The Blackhawk’s Routing (Pat 25)

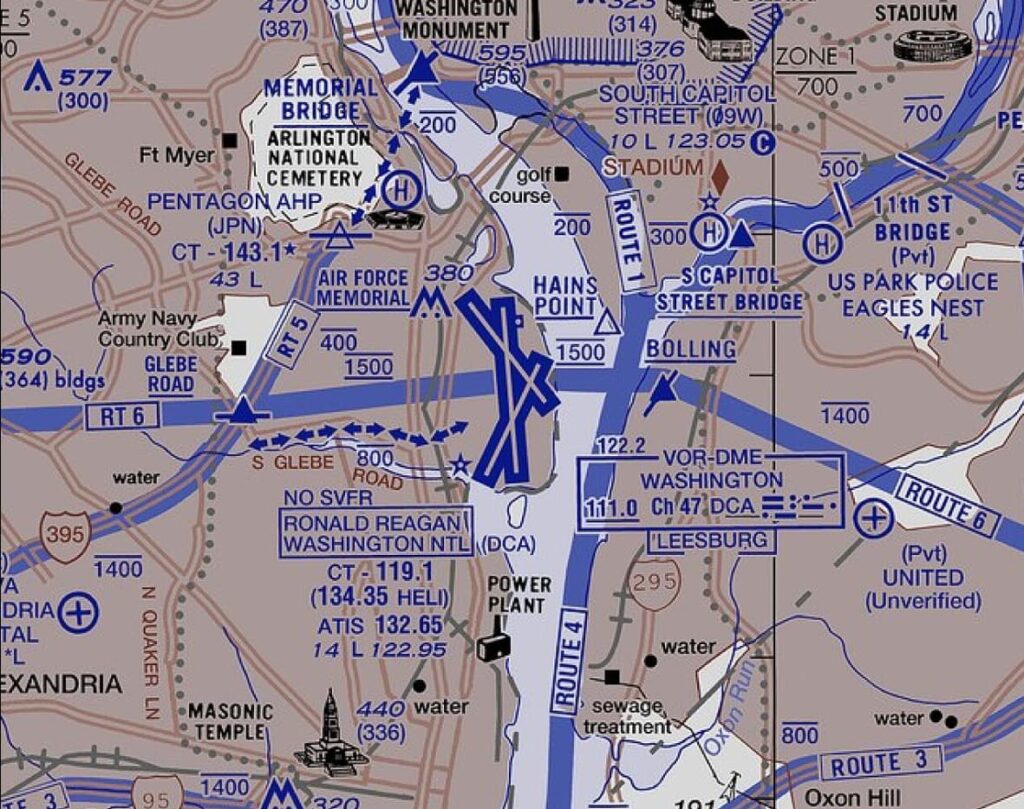

- The UH-60 Blackhawk was following Helicopter Route 1, a designated path along the Potomac River.

- South of Memorial Bridge, helicopters are expected to maintain a maximum altitude of 200 feet unless otherwise instructed

- The helicopter routing follows the river south of Reagan National and crosses the approach path to runway 33 and runway 01.

- This means the controllers likely relied heavily on visual separation as the primary means for deconflicting aircraft in this portion of the airspace.

- The NTSB confirmed that the Blackhawk was using a VHF radio frequency to communicate with Air Traffic Control (ATC), but this was a different frequency than the CRJ was using.

The CRJ-700’s Approach to DCA (Flight 5342)

- Flight 5342 was initially on a visual approach to Runway 01 but due to the heavy volume of traffic into DCA, the controller asked if they could accept an approach to Runway 33 and the pilots agreed.

- The visual approach to Runway 33 is a circling maneuver where the pilots will proceed inbound aligned with Runway 01 and then begin a right turn near the Woodrow Wilson Bridge, followed shortly thereafter by a left turn to align with Runway 33.

- This can be a challenging maneuver, especially at night, and would require the concentrated effort of both pilots.

THE FLIGHT

* all times in pm, Eastern Standard Time

~8:15 The CRJ began descending from its cruising altitude of 37,000 feet

~8:30 The Blackhawk was maneuvering near Leonville, Maryland, before proceeding southbound along designated helicopter routes over the Potomac River toward Washington, D.C.

~8:33 The Blackhawk crew requested clearance to travel along Helicopter Routes 1 to 4, which was approved by air traffic control (ATC).

8:39:10 Potomac Approach cleared the CRJ for the visual approach to Runway 1 at DCA.

8:40:46 The CRJ rolled out of a left turn, established on the approach for Runway 1

8:43:48 The Blackhawk was ~1 nautical mile (NM) west of Key Bridge. The pilot flying indicated they were at 300 feet. The instructor pilot indicated they were at 400 feet. Neither pilot made a comment discussing an altitude discrepancy.

8:44:27 The Blackhawk instructor pilot indicated the aircraft was at 300 feet descending to 200 feet. Simultaneously, ATC offered the CRJ crew the option to switch to Runway 33, which they accepted.

8:45:30 The Blackhawk passed over the Memorial Bridge and the instructor pilot told the pilot flying that they were at 300 feet and needed to descend. The pilot flying said they would descend to 200 feet.

** Note: if the instructor pilot’s altimeter was reading 100 feet higher than the pilot flying’s altimeter, then it’s possible the pilot flying thought they were at the correct altitude while the instructor thought they were high.

~2 MINUTES BEFORE THE COLLISION

8:46:01 ATC issued a traffic advisory to the Blackhawk crew regarding the CRJ’s position, stating, “PAT 25, traffic just south of the Woodrow Wilson Bridge is a CRJ at 1,200 feet circling to Runway 33”.

** Note: The phrase, “circling to Runway 33” was not heard on the Blackhawk’s cockpit voice recorder (CVR), indicating the crew may not have received the full message. This means they might not have expected or planned to look for an aircraft on approach to runway 33.

8:46:29 The CRJ received a 1,000-foot automated altitude callout.

8:46:47 The tower cleared another aircraft for immediate departure from Runway 1.

8:47:27 The Blackhawk passed the southern tip of Hains Point.

8:47:28 The CRJ was at an altitude of 516 feet and began a left turn to align with Runway 33 for landing.

8:47:39 ATC once again asked the Blackhawk: “PAT 25, do you have the CRJ in sight?”

8:47:40 The CRJ received an automated traffic advisory from the Traffic Alert and Collision Avoidance System (TCAS) stating “Traffic, Traffic”

8:47:42 A radio transmission from ATC was heard in both aircraft, directing the Blackhawk to pass behind the CRJ. “Pass behind the CRJ”

** Note: As ATC was making this radio call, the Blackhawk instructor pilot also keyed the microphone, meaning the Blackhawk pilots might not have heard “pass behind the”.

8:47:44 The Blackhawk instructor pilot said “Traffic in sight, request visual separation”, which was approved by the DCA tower controller. The Blackhawk instructor pilot then told the pilot flying they believed that ATC was asking for them to move left toward the east bank of the river.

8:47:52 7 seconds before impact, the CRJ rolled out on final for Runway 33.

** Note: During the left turn to final it would likely have been very difficult for the CRJ pilots to see the dark Blackhawk helicopter below them with a dark river background. If the CRJ First Officer was the pilot flying, his visual focus more likely would have been on the runway to ensure a safe and successful landing and that means spotting the Blackhawk would have been even more difficult for the Captain seated in the left seat.

8:47:58 1 second before impact, the CRJ pilot flying pulled back on the controls and the elevators were deflected near the maximum nose up travel limit. This indicated the CRJ pilots likely saw the Blackhawk at the very last second and made a desperate attempt to avoid the collision.

The radio altitude of the Blackhawk at the time of the collision was 278 feet and had been steady for the previous 5 seconds, indicating they most likely never saw the CRJ prior to the collision.

** Note: There are some discrepancies with the data the NTSB has reviewed for the Blackhawk’s barometric altimeters and that is why they have not released the altitude for the Blackhawk’s route at this time.

THE SWISS CHEESE MODEL

The Swiss Cheese Model, developed by James Reason, is a framework for understanding how accidents occur despite multiple layers of safety barriers. The model envisions each safety barrier as a slice of Swiss cheese, with holes representing potential weaknesses. When these holes align across multiple layers, an accident occurs.

In this accident, several holes in safety barriers aligned that the NTSB will need to consider as part of the investigation:

1. High Traffic Complexity

- The airspace near DCA was highly congested, leading to rapid sequencing changes, tight spacing between aircraft, and increased complexity in maintaining safe separation

- The congestion of aircraft on approach to Runway 1 led to the controller asking the CRJ if they could accept a different runway. Of note, the controller initially asked the aircraft in front of the CRJ if they could accept Runway 1 and they said “unable”. As a result, the controller asked the CRJ (AA Flight 5342).

- The Blackhawk was transiting through airspace heavily used by commercial aircraft, increasing risk.

2. Over-Reliance on Visual Separation

- At night, in a dense urban environment, visual separation is unreliable due to city lights and reduced visibility.

- The Blackhawk pilots were likely using night vision goggles (NVGs), which can restrict peripheral vision, while also making a crosscheck of the altimeter more difficult because the pilot must look under the NVGs to do so.

- It can be easy to mistake one aircraft for another when several aircraft are operating in the same airspace, even while using NVGs.

- The CRJ pilots would likely have a difficult time visually locating the Blackhawk due to the nighttime conditions and their focus on the circling approach maneuver to Runway 33.

3. Altitude Conflict & Last-Minute Instructions

- The Blackhawk’s two barometric altimeters showed conflicting altitude readings, creating uncertainty between the pilots about the aircraft’s actual height.

- Key communications from ATC, such as “circling to Runway 33,” may not have been fully received by the Black Hawk crew due to radio interference, resulting in the crew possibly not expecting to see the CRJ on approach to Runway 33.

- The Blackhawk crew accepted responsibility for visual separation, but NVGs and urban lighting likely made it difficult to accurately identify and track the CRJ.

- The CRJ was descending into the Blackhawk’s altitude layer.

- The Blackhawk may have been flying higher than the prescribed 200-foot limit.

- ATC’s late attempt to clarify the deconfliction by instructing the Blackhawk to “pass behind” the CRJ was likely not fully received due to radio interference.

- ADS-B Out Non-Functionality: The Blackhawk was equipped with ADS-B Out, yet it was not transmitting at the time, possibly limiting positional situational awareness.

FINAL THOUGHTS

This tragic accident underscores the challenges of managing mixed-use airspace in highly congested areas. The fact that helicopter routes intersect directly with final approach paths for commercial jets, relying on visual separation is concerning.

The FAA has already implemented temporary restrictions on helicopter flights in the area, but long-term changes must be considered, including stricter ATC oversight for helicopters in mixed-use corridors.

Ultimately, this accident highlights the necessity of proactive rather than reactive safety measures. The aviation industry cannot afford to wait for accidents to expose vulnerabilities; instead, airspace management must evolve to prevent tragedies like this from occurring in the future.