A Routine Flight Turns Deadly

On September 8, 2019, an 82-year-old pilot departed from Richland, Washington, in his Piper PA-32-300, headed for Ontario, Oregon. It was supposed to be a straightforward visual flight rules (VFR) trip, one the pilot had likely taken before.

About 30 minutes into the flight, things started to go wrong. The aircraft veered off course, and its altitude and speed became erratic. Witnesses camping near the crash site heard a low-flying airplane pass overhead, but they couldn’t see it through the fog and rain. Moments later, they heard a loud pop—then silence.

The plane had crashed into a steep mountain slope near La Grande, Oregon, killing the pilot instantly.

The Pilot’s Experience

The pilot was highly experienced, holding a commercial pilot certificate with ratings for single-engine land, multi-engine land, and an instrument rating. He was also a certified flight instructor for both single and multi-engine aircraft.

His logbooks were unavailable, but records showed he had 2,243 total flight hours—all in the same model of aircraft. However, there was no record of him completing an instrument proficiency check within the past year. This meant it was unclear whether he was legally current or prepared for instrument flying.

The Flight Path and Final Moments

GPS data showed that the plane first climbed to 6,500 feet. It flew straight toward Ontario. But about 70 miles into the trip, it started to drift south.

In the last five minutes, the aircraft’s movements became erratic.

It climbed to 7,444 feet while slowing from 140 knots to 53 knots. That is a dangerous combination. Slow speed at high altitude can cause a stall. The plane then entered a steep descent. It crashed just 450 feet from its last recorded GPS position.

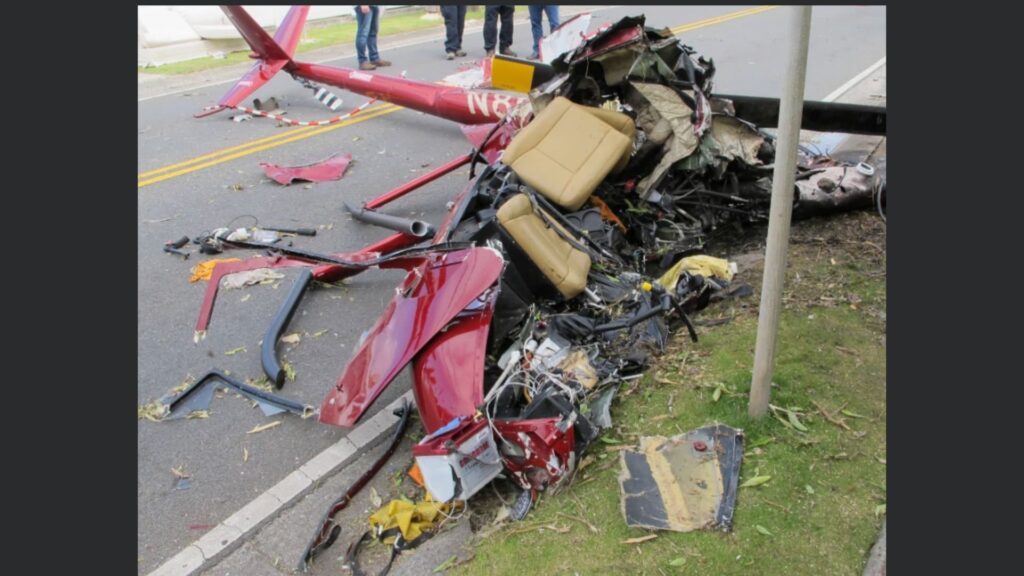

The damage showed it hit the ground at high speed.

What Went Wrong?

1️⃣ Flying VFR Into IMC

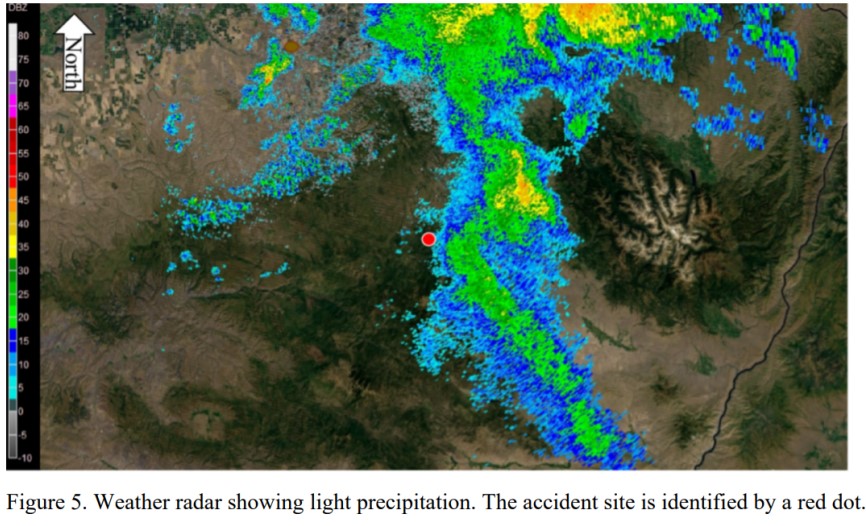

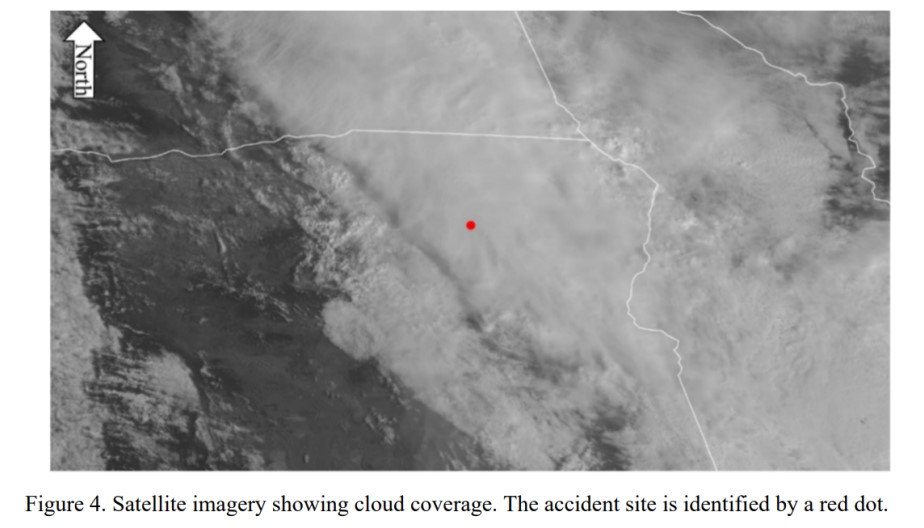

Weather reports near the departure and destination airports showed clear skies. But an AIRMET warning of mountain obscuration and poor visibility was active in the accident area.

Satellite images confirmed thick clouds over the mountains. Witnesses near the crash site reported rain and heavy fog.

The pilot was flying under visual flight rules, or VFR. This means he needed to see the ground or horizon to navigate. When he entered the clouds, he lost his visual reference points. Pilots in this situation must rely on their instruments. Without recent practice, this can be difficult.

The plane’s erratic speed and altitude suggest the pilot became disoriented. He likely lost control of the aircraft.

2️⃣ Instrument Experience Matters

The pilot held an instrument rating and was a flight instructor, but there was no record of an instrument proficiency check in the past year.

Even skilled pilots can struggle in IMC if they haven’t practiced instrument flying recently. Without a clear visual horizon, it’s easy to become disoriented and lose control.

This is why instrument currency is critical—an outdated skill set can be just as dangerous as no training at all.

3️⃣ No Mechanical Failures

The Piper PA-32-300 was fully equipped for instrument flight, with a Garmin GNS-430W GPS and autopilot. However, it’s unclear whether the pilot attempted to use these systems during the emergency.

Wreckage analysis found:

✔ No engine or mechanical failures

✔ No evidence of in-flight breakup

✔ Impact forces consistent with high-speed descent

The crash wasn’t due to equipment failure—it was a loss of control in IMC.

Lessons from This Tragedy

🛑 1. VFR into IMC is one of the most dangerous mistakes in aviation.

Pilots must be aware of deteriorating weather and turn back or land before entering clouds.

📖 2. Having an instrument rating isn’t enough—staying proficient is key.

Regular training helps maintain the muscle memory and quick decision-making skills needed for instrument flight.

🖥 3. Autopilot and GPS can be lifesavers—but only if used properly.

In low visibility, an autopilot can keep the aircraft stable while a pilot regains situational awareness.

This accident is a tragic reminder of how quickly VFR flights can go wrong in poor weather. Recognizing the warning signs and making the right decision early can mean the difference between life and death.

💬 Have you ever faced unexpected weather while flying? How did you handle it? Let’s discuss in the comments!

5 Comments

Other critical skills also deteriorate without practice. So sad.

82 is quite old to be flying.

Im not trying to be ageist or

saying the pilot wasn’t fit to

fly or suffering from

dementia, because there are

people in their early 80’s who

can still be perfectly safe.

But I do feel someone

approaching 80 needs to

have an assessment to

check they are still medically

fit and have fast enough

reactions to be safe..This

should include instrument

checks if they want to fly in

IMC as well as a check ride

as they would have done to

gain their license initially.

My only experience of VFR into IMC happened on a night flight from S. Texas (just north of Corpus Christie) to San Antonio. I was about 15 min. into the flight at about 2,500′ when I hit a bank of clouds. I had had some emergency IFR training while getting my PPC, so I was able to stay wings level long enough to radio ATC.

I said, “I just hit some clouds and I’m not IFR rated. How far can I safely descend?”

ATC radioed that I had plenty of room below me – about 750′ – before I got close to anything. I safely got out of the clouds and made the rest of trip with no problems.

I started IFR training the next day. Ironically, it took me *six years* to ultimately check out. I moved a lot back then, and had to keep restarting my training. I had to take the written three times because it’s only good for two years at a time.

PS. I almost quit just before I passed my checkride. I had “hit the wall,” and didn’t feel like I was getting anywhere. My lovely and brilliant wife told me that she wouldn’t let me quit; that I’d worked too hard for too long to just walk away.

I passed my checkride 10 days later. 😀

Perhaps during a Flight Review, the instructor could test the pilot’s proficiency on handling IFR conditions by intentionally flying in clouds…..and see how the pilot reacts…

A sad story. A good reminder to us to

avoid those situations