A highly experienced helicopter pilot, a well-equipped Bell 407, and a seemingly straightforward repositioning flight—all of it unraveled in under 90 seconds after takeoff. This tragic October 2023 accident reminds us that even the most seasoned aviators aren’t immune to the dangers of night flight, spatial disorientation, and lapses in cockpit discipline.

The Setup: A Routine Turned Risky

On October 8, 2023, a 73-year-old commercial pilot—rated in helicopters, fixed-wing aircraft, and a certified instructor—prepared for a night repositioning flight from a remote landing site in Croydon, New Hampshire, to Quonset State Airport (OQU) in Rhode Island. He had landed at the off-airport site two days prior after being grounded by weather and returned on the 8th to retrieve the helicopter after playing a round of golf.

The helicopter was a 2009 Bell 407 (N802JR), operated under Part 91 and equipped with a full suite of safety tech, including the HeliSAS stability augmentation and autopilot system, an onboard image recorder, and a spotlight. Despite these resources—and the pilot’s 13,780 flight hours—something went terribly wrong.

A Closer Look at the Pilot

- Certificate: Commercial (airplane single-engine land/sea, multi-engine land, helicopter), CFI for airplanes and helicopters

- Instrument Ratings: Airplane and helicopter

- Total Flight Time: Approx. 13,780 hours

- Time in Type (Bell 407): 1,377 hours

- Last Medical Exam: October 2022 (Class 2, with waivers)

- Age: 73

Notably, while the pilot had recent recurrent training under Part 135, including unusual attitude recovery, most of his recent flight time had been in daylight conditions. The operator didn’t track night currency, and there was no regulatory requirement to do so for Part 91 positioning flights.

The Flight: “It’s Too Dark”

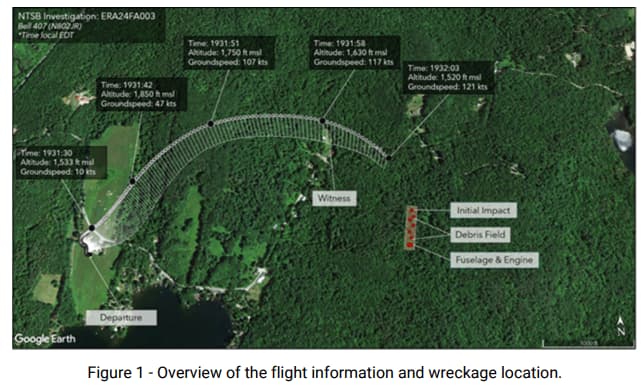

At 7:31 p.m., the pilot lifted off vertically into the night sky. Within 15 seconds, he was already expressing doubt. “Ah [expletive], it’s too dark,” he said aloud. The onboard recorder showed the helicopter quickly accelerating into unusual attitudes—steep nose-down, hard right bank, uncoordinated flight—and red chevrons began flashing across the primary flight display.

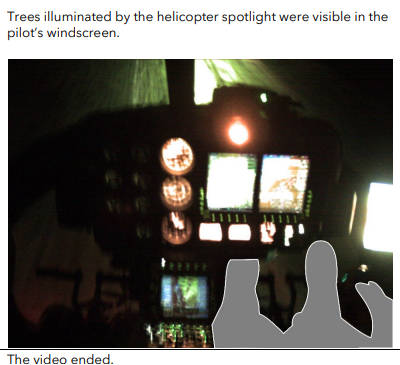

He asked aloud, “What am I doing?” as he made large, erratic cyclic inputs. Despite warnings from the terrain awareness system and rapidly increasing airspeed, the aircraft continued to pitch down in an extreme right bank. Just before impact, the spotlight illuminated the treetops. The recording ended as the helicopter crashed into the forest.

The wreckage was discovered several hours later, with the pilot fatally injured. The helicopter was destroyed. No mechanical failures were found.

What Went Wrong

The NTSB’s final report was unequivocal: the crash was the result of spatial disorientation in dark night conditions. Key contributing factors included:

- Lack of recent night flying experience

- Improper cockpit lighting: The pilot increased display brightness before flight but never dimmed it—a known hazard for night ops, causing glare and windshield reflections.

- Failure to use the HeliSAS system: Though trained and experienced in its use, the pilot never activated the stability system, which might have helped arrest the unusual attitudes.

The NTSB also confirmed the pilot had a history of cardiovascular disease, including prior bypass surgery. However, video and flight data didn’t indicate a medical event, and the cause of death was blunt force trauma from the crash.

Dark Night, No Horizon

The crash happened under dark night conditions, with the moon 23° below the horizon and only 28% illuminated. There were no clouds or precipitation, but also no visible horizon—just a black void above and dark terrain below.

This absence of visual reference is where spatial disorientation thrives. Without a clear horizon, the body’s inner ear can easily misinterpret motion, leading the pilot to “feel” level flight even when the aircraft is in a dangerous attitude. The FAA’s own handbooks warn of this exact scenario, especially for pilots lacking recent night experience.

What Could Have Helped

- Engaging HeliSAS: The helicopter’s stability augmentation system was in standby throughout the flight. This system could have leveled the helicopter automatically—if only the pilot had engaged it.

- Dimmer Cockpit Lights: FAA night-flying guidance urges pilots to dim interior lighting to match ambient darkness. Bright lights inside reduce the pilot’s ability to detect terrain and other hazards outside.

- Assessing Currency Honestly: While legal, flying at night without recent practice is a known risk. Self-assessment is crucial—especially when planning off-airport or solo operations in remote areas.

Final Thoughts

This accident wasn’t due to engine failure, mechanical malfunction, or external weather. It was a textbook case of spatial disorientation—something that can affect any pilot, no matter how experienced.

When the pilot said, “It’s too dark,” he knew he was outside his comfort zone. But by then, it was already too late.

This tragedy is a stark reminder of the silent threats in aviation—the ones that come from inside the cockpit, from our own limitations, and from underestimating the invisible dangers of the night.

5 Comments

Generally I have tended to see spatial disorientation as not that big of a deal. Just look at your instruments. I say this as a non-pilot. But incidents like this make me take spatial disorientation more seriously. This is kind of frightening. It’s hard to understand someone with so much experience being so ‘easily’ confused.

When I was a student pilot, I asked my instructor to let me fly through cloud so that I could experience spatial disorientation, not just learn about it in ground school. He agreed and I climbed into the cloud and, while he watched closely, I set up the aircraft for level flight and he told me to maintain altitude and course. After about 30-40 seconds, he asked, “Where are you going?” I replied that I was following his instructions. “You’re in a descending left turn,” he announced and took control. We repeated the exercise 4 or 5 times and I was astonished how easy it is to disbelive your instruments when the signals from your brain are so strong. One of the most powerful lessons I ever learned.

Mike- Spatial Disorientation is a real killer, especially when extensive experience creates confirmation bias in your judgement. Those acquired skills can and will rise up to bite you at some point, if you don’t keep reminding yourself that you are NOT bullet-proof.

With sufficient instrument time in simulators and under a hood with and instructor, looking at the instruments will relieve disorientation, the same as in vfr conditions looking at the real horizon.

In a night IFR landing at LAX in my Bonanza under radar vectors, my artificial horizon tumbled. I was able to recognize the problem in spite of disorientation and switch to needle ball and air speed.

There was a classic, real-world example of how training and experience can save your bacon. An important take-away from this helo event, was that lots of time in the logbook doesn’t provide you with a perfect set of bullet-proof skills. I was very fortunate to have an instructor that believed in putting you under the hood, with the blinders down, and then she would put the aircraft in an unusual attitude after doing some maneuvers to really get those ears confused. Then you were instructed to put the blinders up and immediately put the aircraft into a wings level, steady altitude or one she specified to change to (to increase the difficulty). This would be repeated throughout the remainder of my primary training. It was a great technique, intended to get you onto the instruments and ignore what your seat was telling you about the attitude of the airplane. Since then, I’ve found myself in conditions where those skills were a life-saver. The typical summer conditions along the Mass, RI coast and out to the islands (a frequent play ground) are often very hazy making the horizon nearly invisible, especially on days with high humidity and light winds.