On August 15, 2019, a Textron Aviation 680A Citation Latitude (N8JR) touched down at Elizabethton Municipal Airport (0A9) in Tennessee. What should have been a routine landing quickly unraveled into a series of bounced touchdowns, a failed go-around attempt, a runway excursion, and a post-crash fire that destroyed the aircraft. Thankfully, the two pilots and three passengers survived, though the event serves as a stark reminder of the importance of stabilized approaches and proper landing execution.

A Flight That Started Smoothly

The crew, consisting of a highly experienced pilot and copilot, departed Statesville Regional Airport (SVH) in North Carolina at 3:19 PM local time. Their flight plan was simple: drop off one passenger in Elizabethton before continuing to San Antonio, Texas. The aircraft, weighing just below its maximum landing weight, climbed to 12,500 feet and proceeded uneventfully—until they reached the approach phase.

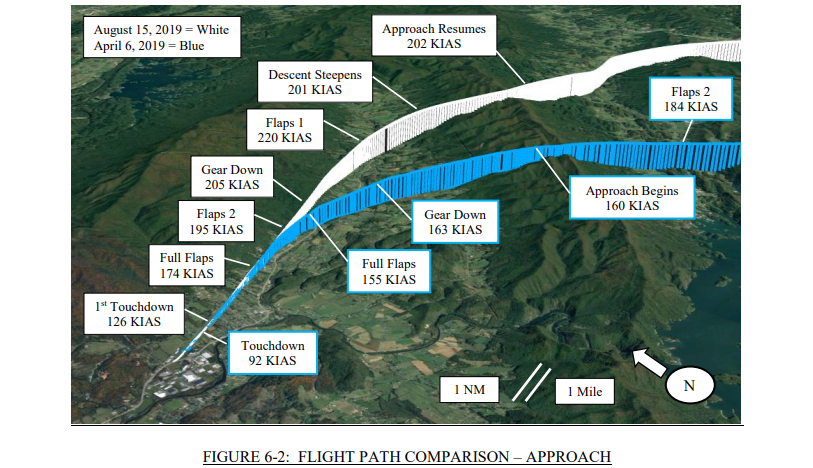

The trouble began when the pilots struggled to visually acquire the airport while navigating around clouds. As they crossed a ridge, a Terrain Awareness and Warning System (TAWS) alert sounded—an early indication that things were not as controlled as they should be. Soon after, the aircraft’s airspeed crept significantly above the target reference speed (Vref), and despite multiple verbal acknowledgments from the crew about being too fast, they pressed on.

An Unstable Approach Ignored

At 1536:12, the pilot called for flap extension, and by 1536:50, the landing gear was deployed. Yet, their airspeed was still too high, and descent rates exceeded the recommended limits. Five seconds before touchdown, the aircraft was descending at an alarming 1,500 feet per minute—well beyond the maximum 600 fpm allowed in the aircraft flight manual (AFM).

At this point, the pilot asked his copilot: “Do I need to go around?” The response: “No.”

This was a critical decision point. The pilots knew they were coming in too fast and too steep, yet they opted to land rather than executing a go-around.

The Four-Touchdown Nightmare

When the aircraft first touched down, it was still 18 knots above Vref. The pilot skipped a crucial step—extending the speedbrakes, which would have significantly aided in slowing the aircraft. Instead, he attempted to deploy the thrust reversers immediately. However, since the aircraft bounced almost immediately, the system logic prevented them from unlocking.

The aircraft bounced three more times. On the third touchdown, all three landing gear were briefly on the ground, allowing the thrust reversers to unlock. But the plane bounced again before they could be fully deployed. At this point, the pilot attempted to go around—something explicitly prohibited after thrust reverser deployment per the AFM. Unfortunately, the system logic prevented the engines from increasing power because the reversers were not properly stowed.

A Crash Course in Decision-Making

With the aircraft now aerodynamically unstable, the final touchdown was hard—registering 3.2 Gs. The right main landing gear collapsed, the aircraft veered off the runway, crossed an embankment, crashed through a chain-link fence, and came to rest near a highway. A post-crash fire erupted, but all five occupants managed to escape—though only after struggling to open the emergency exits due to structural damage.

Post-accident examinations found no mechanical failures—the aircraft was in perfect working condition. The cause? Poor decision-making in a high-stakes moment.

Key Takeaways

- Unstable Approach = Go Around

The pilots knew they were too fast and had a high descent rate, yet they chose to continue. A go-around should have been initiated well before touchdown. - Commitment to Stop (CTS) Point Awareness

Once the thrust reversers were deployed, a go-around was no longer an option. The concept of a CTS point—where pilots must commit to landing—was not understood by the crew, despite FAA guidance encouraging its adoption. - Spoilers (speedbrakes) First, Then Thrust Reversers

The aircraft manufacturer explicitly stated that spoilers have a greater stopping effect than thrust reversers. Had the pilot deployed them immediately upon touchdown, the aircraft likely would have stopped safely on the runway. - Crew Resource Management (CRM) Matters

The copilot was the pilot-in-command’s direct supervisor, but both denied that this dynamic affected decision-making. Regardless, hesitation and miscommunication contributed to the failure to execute a go-around when it was most needed.

Final Thoughts

This accident underscores the fundamental principle of stabilized approaches—if the aircraft is not in a safe landing configuration, go around. Had the pilots recognized the warning signs and acted decisively, this could have been just another uneventful flight.

For those flying high-performance jets, the lessons here are invaluable: respect your aircraft’s limitations, follow procedures, and when in doubt—go around.