A Night Flight Turns Catastrophic

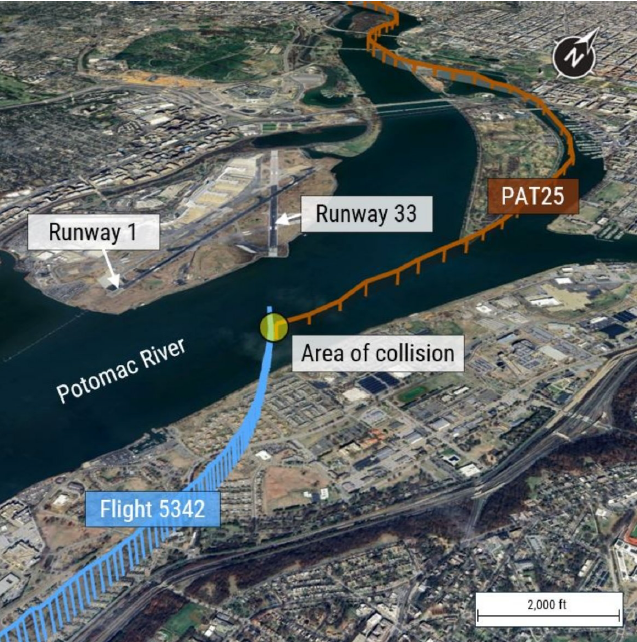

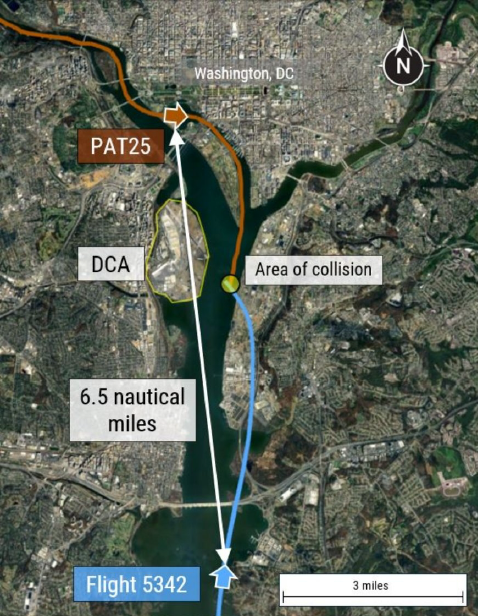

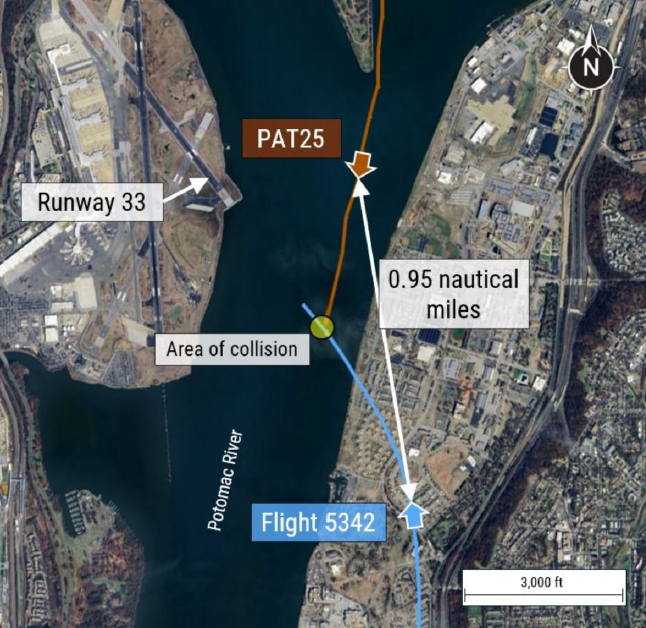

On the night of January 29, 2025, what should have been a routine approach into Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport (DCA) turned into an unimaginable disaster. A U.S. Army Sikorsky UH-60L Blackhawk helicopter—callsign PAT25, collided midair with PSA Airlines CRJ700, operating as Flight 5342, —just half a mile from the airport. Within seconds, both aircraft plunged into the icy Potomac River, claiming the lives of 67 people.

The Flight Crews: Experienced, But Caught in a Fatal Situation

Both aircraft were flown by qualified and experienced pilots:

PSA Airlines Flight 5342 (CRJ700) Crew

- Captain: 3,950 total flight hours, with 3,024 hours in the CRJ700

- First Officer: 2,469 total flight hours, with 966 hours in the CRJ700

- Both pilots held Airline Transport Pilot (ATP) certificates

The captain was the pilot flying, while the first officer was monitoring.

PAT25 (UH-60L Blackhawk) Crew

- Instructor Pilot (IP): 968 total hours, with 300 hours in the UH-60L

- Pilot: 450 total hours, with 326 hours in the UH-60L

- Crew Chief: 1,149 total hours, all in UH-60 helicopters

The Black Hawk crew was conducting a night vision goggle (NVG) standardization evaluation—a routine Army “checkride” for the Pilot. The NTSB didn’t talk about recency of experience for the Blackhawk pilots and whether or not that was a factor in this mishap.

The Timeline: A Chain of Small Errors With Deadly Consequences

8:43 PM – A Last-Minute Runway Change

- Flight 5342 initially received clearance for Runway 1.

- Due to spacing issues with the aircraft in front of and behind them, the tower asked if they could accept Runway 33 instead.

- The crew accepted.

8:46 PM – ATC Warns PAT25 About Traffic

- The controller tells PAT25 that a CRJ is at 1,200 feet, “circling” to Runway 33.

- Key issue: The word “circling” was not captured on the helicopter’s cockpit voice recorder (CVR), meaning they may not have understood the CRJ’s flight path.

8:46:08 PM – PAT25 Requests “Visual Separation”

- The helicopter crew requests and receives approval to maintain visual separation from the CRJ.

- At this point the helicopter was ~6.5nm away from the the CRJ, making it difficult to positively identify the CRJ

- Issue: PAT25’s view was limited by night vision goggles, which reduce depth perception and peripheral vision.

8:47:39 PM – A Last-Minute ATC Directive Gets Missed

- The controller asks PAT25 if they still have the CRJ in sight—a conflict alert is heard in the background.

- 4 seconds later, ATC instructs PAT25 to “pass behind the CRJ.”

- Tragic Miscommunication: A simultaneous radio transmission (mic key press) from PAT25 likely blocked part of the controller’s message. However, the Blackhawk crew reported they had the CRJ in sight.

8:47:59 PM – The Collision

- The CRJ’s left wing strikes the Black Hawk’s tail rotor, severing it instantly.

- The helicopter spins out of control and crashes into the river.

- The CRJ rolls violently, breaking apart before hitting the water.

Helicopter Altitude and Altimeter Discrepancies

- Altitude Discrepancies Between Pilots

- The Instructor Pilot (IP) and the Pilot had conflicting altitude readings.

- At 8:43:48 PM, the pilot stated they were at 300 feet, while the IP indicated 400 feet.

- Shortly after, the IP instructed the pilot to descend to 200 feet, following Helicopter Route 1 altitude restrictions.

- Barometric Altimeter Inconsistencies

- The left-seat pilot’s altimeter set between 29.88 and 29.89 inches of mercury (inHg).

- The right-seat pilot’s altimeter was set to 29.87 inHg.

- These minor differences typically would not result in a 100ft altitude difference between the two altimeters.

- Impact on Situational Awareness

- Small altitude variations (e.g., 200 vs. 300 feet) were not verbally reconciled between the pilots.

Why Did This Happen? The Investigation’s Key Findings

There are multiple safety concerns that made this accident possible.

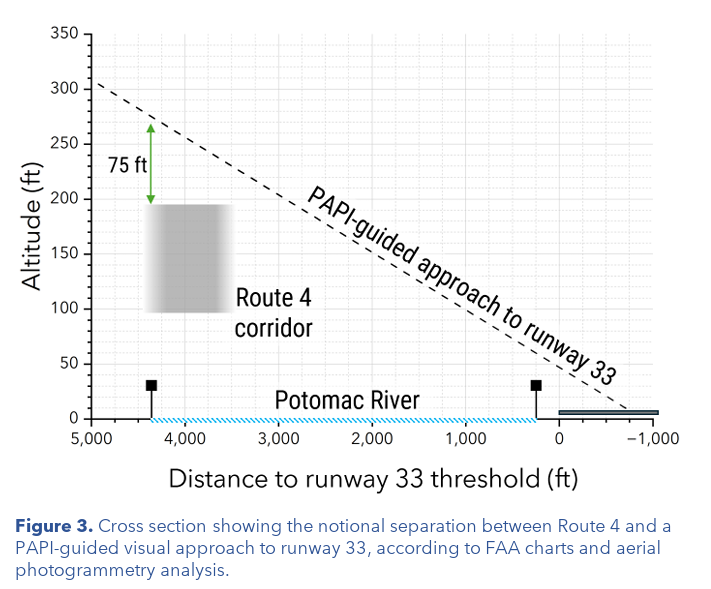

1. Dangerous Overlap Between Helicopter Routes and Commercial Jet Approaches

- Helicopter Route 4 runs directly below the final approach path for Runway 33.

- At just 200 feet altitude, helicopters are dangerously close to arriving jets.

- A review of 2011-2024 flight data showed:

- At least one TCAS resolution advisory (RA) per month due to helicopters.

- In over half of these instances, the helicopter may have been above the route altitude restriction

- Two-thirds of those events occurred at night.

- A review of commercial operations at DCA from Oct 2021 – Dec 2024 revealed:

- 944,179 operations

- 15,214 instances of near-misses between jets and helicopters (less than 1nm lateral and/or less than 400 feet vertical separation

- 85 recorded events where separation was less than 1,500 feet laterally and 200 feet vertically.

2. The Risks of Separate ATC Frequencies for Jets and Helicopters

- Flight 5342 and PAT25 were on different radio frequencies, meaning they couldn’t hear each other’s communications.

- The helicopter crew may not have fully understood the CRJ’s flight path.

3. TCAS Limitations in Urban Airspace

- The CRJ’s TCAS issued a “Traffic” alert, but below 900 feet, TCAS does not issue automatic “Climb” or “Descend” instructions.

- The helicopter had no TCAS display, meaning it relied entirely on visual separation—a serious limitation at night.

4. Human Factors: Night Vision and Workload Management

- Night vision goggles (NVGs) improve visibility but limit peripheral vision.

Immediate Safety Actions Taken

The tragedy prompted immediate FAA and NTSB action:

- January 31, 2025: The FAA banned helicopters from flying over the Potomac River near DCA unless for law enforcement, medical, or presidential missions.

- March 7, 2025: The NTSB issued two urgent safety recommendations:

- Prohibit helicopters from using Route 4 when Runway 33 is active.

- Establish an alternate helicopter route.

These actions aim to permanently separate commercial jet and helicopter traffic.

Final Thoughts: A Tragedy That Must Never Be Repeated

The midair collision over the Potomac was avoidable. A combination of miscommunications, airspace design flaws, and human factors contributed to this disaster but the NTSB is still conducting their investigation to produce a final report and probable cause.

20 Comments

Hi Hoover.

I really enjoyed your livestream about this accident. The swiss cheese off the approach end of 33 at DCA certainly has a lot of holes in it, but there’s another aviation fact that is somewhat related and I wonder what your thoughts are. IFR and VFR separation is nominally 500 feet and we’re all comfortable with that. But VFR pilots are allowed +/- 300 feet in altitude and IFR reduces that to 100 feet. If things all go wrong and the VFR guy is 300 feet high and the IFR guy is 100 feet low, we have a separation of only 100 feet! That isn’t a lot different than the 75 foot separation at DCA, is it? Yet we get away with it for years on end without having midair’s. So what’s the best solution to deconflict traffic on that approach? One possibility might be to stop allowing “visual separation” for the helicopters and have ATC issue specific instructions to the crossing helicopter traffic. I just wondered what your opinion was.

When you do not have sufficient separation between the aircraft during the landing phase, you should have them go around by passing them on the approach to put them in a holding pattern and not divert them less than 6.5 miles from runway 01 (7169 feet – 2185 meters) to runway 33 which is shorter (5204 feet – 1586 meters) and even the same one intersects with two other runways (Rwy-22, Rwy-19). Furthermore, the instrument approach to runway 33 is RNAV (GPS) RWY 33 asking an aircraft on approach and moreover stable on the ILS glide path Rwy-01 at 6.5 miles (about 1900 feet – 2000 feet AGL) of the runway 01 head to divert to runway 33 was the first mistake.

Thank you for top class safety videos fot pilots .I am PPL with lapsed IMC and 600 hours logged.

Thanks so much for the time you spent putting this together. As a former controller it’s clear to me that the local controller in the tower should have told the chopper to hold his position since the arriving aircraft was on a modified left base to 33. This was a controller error in my opinion no matter that the chopper had the CF-J “in sight”. It was at night! It is shocking that there were so many close calls over that 12 month period and no action was taken by the FAA. I am sure that many controllers complained about this process!

The FAA handbook on ATC (7110.65) says this about visual separation (para 7-2-1):

“3. A pilot sees another aircraft and is instructed to maintain visual separation from

the aircraft as follows:

(a) Tell the pilot about the other aircraft including position, direction and,

unless it is obvious, the other aircraft’s intention.

(b) Obtain acknowledgment from the pilot that the other aircraft is in

sight.

(c) Instruct the pilot to maintain visual separation from that aircraft.

(d) Advise the pilot if the radar targets appear likely to converge.

Issue this advisory in conjunction with the instruction to maintain visual separation, or

thereafter if the controller subsequently becomes aware that the targets are merging.”

Should ATC have been warning the aircrew that their targets were converging?

I’m a retired army CW4, former army rotary & fixed wing pilot, and a former 2nd ID division aviation safety officer with accident investigation experience. So here’s my thoughts and questions about risk management procedures for the unit and crew of the army helicopter.

First of all (unless things have changed since I retired in 2010), army flight planning SOP includes a risk analysis & management plan prior to every flight. And high risk missions always required an elevated chain of command approval prior to departure. So one of my first questions for the unit would be, “What was the risk level noted by the crew and who approved it?” That’s just the starting point to determine the obvious systemic problems within the unit which led to the crew’s lack of situational awareness. My investigation would try to determine how/why ‘the IP’ didn’t recognize, communicate, and act on the unsafe operation of the aircraft.

I’d also want to verify the unit’s safety officer had already identified the aircraft separation as a high risk. And finally, what risk abatement procedures did the chain of command have in place. Bottom line, any army safety officer knows that portion of the route was an accident waiting to happen without implementing specific additional pilot requirements.

Thanks for passing the report along, Hoover; the conclusions coincide with my initial thoughts of why would you play around with one or Murphy’s basic laws? Was it really necessary to have helicopters or whatever crossing a busy final approach; particularly at night? As I mentioned before: taking a course on terrorist management with the FBI, the instructor told us back in 1990 the ideal weapon for terrorist actions where jet transport taking off full of fuel; and yet we had to wait for major fatality to change things. In the Potomac case, all those near misses and no action? But then, I never in my wildest dreams could I imagen the land of my forefathers becoming a banana republic with all the government waste. It’s just mind boggling.

Since the helicopter was on the right side of the airliner, how did the LEFT wing of the airliner clip the tail rotor?

I’ll have to go back and look at the report…it’s possibly a typo

Yes, I wondered the same thing.

Count me in on that. I thought it was just my noggin’ missing the obvious. Good to know some comrades had the same conclusion. Oh, btw Hoover, I love the accident scenario of the week. If possible, would an addendum to this site’s information for us to post some answers be difficult?? Just so we can get chewed on by our fellow aviators.

I can imagine the left wingtip descending into the tail rotor immediately before the two aircraft might have missed each other entirely.

Hoover, you are a legend. I recently used this accident as a safety share with my team and just sent out these updates. I am a GA pilot but work in public transport in Australia and accidents like this in aviation help us improve safety anywhere there are big things moving people around. It literally blew my mind the amount of near misses without addressing the safety risk. Keep up the excellent work helping improve safety all over the world accross industries!

Awesome! Glad to hear it helped give more info to your team!

It would appear that the risk of a fatal collision was unacceptably high by orders of magnitude. What I don’t understand is how different government regulators seem to operate to widely differing safety standards; yet a human life lost is exactly that, irrespective of the nature of the accident. In the U.K. (and I’d guess it’s likely to be similar in the U.S.), the nuclear regulator stipulates rules based on safety principles that if transferred to the aviation field would probably equate to the risk of such a collision in a year being less than 1 in a million. If the risk was estimated to be higher than this value then either suitable mitigations would need to be put in place to reduce the risk to below the tolerable level or the regulator would withdraw the airport’s licence to operate.

David-

Your reference to Nuclear Regulators caught my attention. I’m retired from the Nuclear Power business after 23 years as a civilian (SRO licensed) and a 6 year hitch in Navy Admiral Rickover’s Canoe Club in submarines. I was a Navy Certified Instructor (Officer and Enlisted) and was on the Accident Assessment team during my civilian tenure. I also participated in a full scale, one week assessment as a Senior evaluator on an Institute for Nuclear Power Operations team, visiting another plant.

ALL civilian procedures, normal, abnormal and emergency are evaluated by an entire team of multi-discipline plant management before being published. Oddly enough, the nuclear power business had just finished adapting CRM as a mandatory class for all licensed operators. Some of our printed materials for that, still had the airline’s logo on them at the time, since it was a pilot program still.

Mark,

Thanks. It’s encouraging to hear that different regulators do take best-practice from across different safety-related activities. Nevertheless it appears that the bar is set at different levels when it comes to minimising bad outcomes. I’d say it’s at least partly to do with the public’s perception of risk, resulting in illogical outcomes such as death and injury being more tolerable depending on the circumstances of the accident, so dying in a plane impact is more acceptable than a nuclear accident, and a road traffic fatality barely figures in the public’s list of worries.

Hoover, I always enjoy how you simplify the usage of words you use to describe the air disasters you cover. Great Job and Thank You for your Military Service.

HOWEVER…

Why 0′ Why does the FAA “WAIT” until a disaster waiting to happen, really happens to deal with the incoming/outgoing air traffic situations at this airport?

Immediate Safety Actions Taken:

The tragedy prompted immediate FAA and NTSB action:

January 31, 2025: The FAA banned helicopters from flying over the Potomac River near DCA (unless) for law enforcement, medical, or presidential missions.

March 7, 2025: The NTSB issued two urgent safety recommendations:

Prohibit helicopters from using Route 4 when Runway 33 is active.

Establish an alternate helicopter route.

These actions aim to permanently separate commercial jet and helicopter traffic.

What’s up, I check your blog like every week. Your writing style is awesome,

keep up the good work!

If some one wants expert view on the topic of blogging after that i advise him/her to pay a

visit this web site, Keep up the nice job.