A Flight That Should Have Been Routine

On April 19, 2024, a Cirrus SR22T (N51FM) was on an instrument approach to Paso Robles Municipal Airport (KPRB) in California. The aircraft had departed from Big Bear City Airport (L35) under IFR (Instrument Flight Rules), carrying a 50-year-old private pilot receiving instruction, a 23-year-old flight instructor, and a passenger.

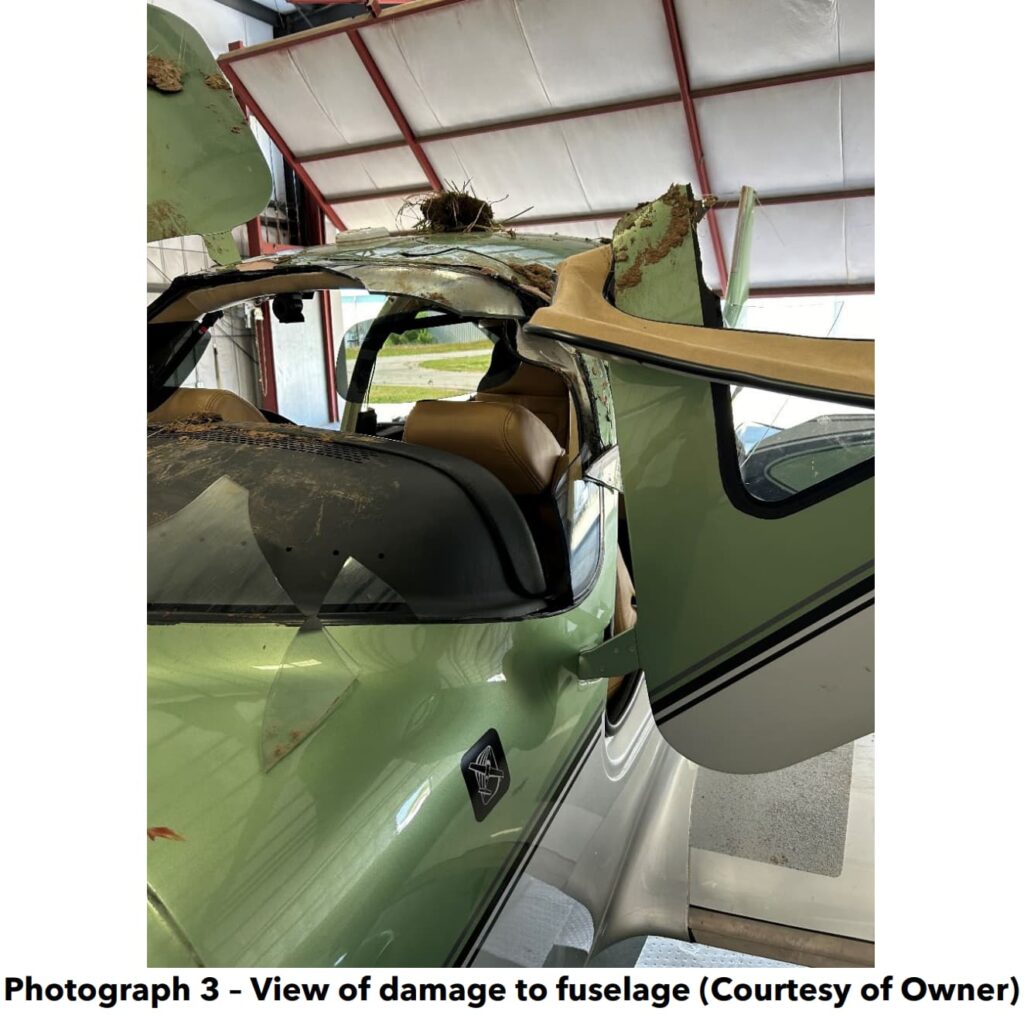

What started as a normal IFR flight ended in a runway excursion and crash landing. The aircraft flipped over in a field just off the runway, causing serious injuries to the pilot under instruction and minor injuries to a passenger. The flight instructor escaped unscathed.

This accident wasn’t just about a bad landing—it was a chain reaction of misjudgments, beginning with improper approach planning and ending with a failed last-second course correction.

Who Was Flying?

The accident flight was a training session. The pilot receiving instruction held a private pilot certificate with a single-engine land rating but didn’t have an instrument rating. He had logged 270 total flight hours, all in the Cirrus SR22T, with 106 hours as pilot-in-command. However, in the previous 90 days, he had only flown four hours.

The instructor, who was 23 years old, held commercial and flight instructor certificates for single-engine and instrument airplanes. She had accumulated 438 total flight hours, with 114 in the SR22T. She had flown 14 hours in the last 90 days and 10 hours in the past 30 days.

Weather and Airport Conditions

The weather likely played a minor role in this. Paso Robles had 10 miles of visibility, light winds, and scattered to broken clouds at 800 feet AGL. The aircraft was executing an RNAV approach to Runway 19, which is 6,008 feet long and 150 feet wide, with dry asphalt conditions.

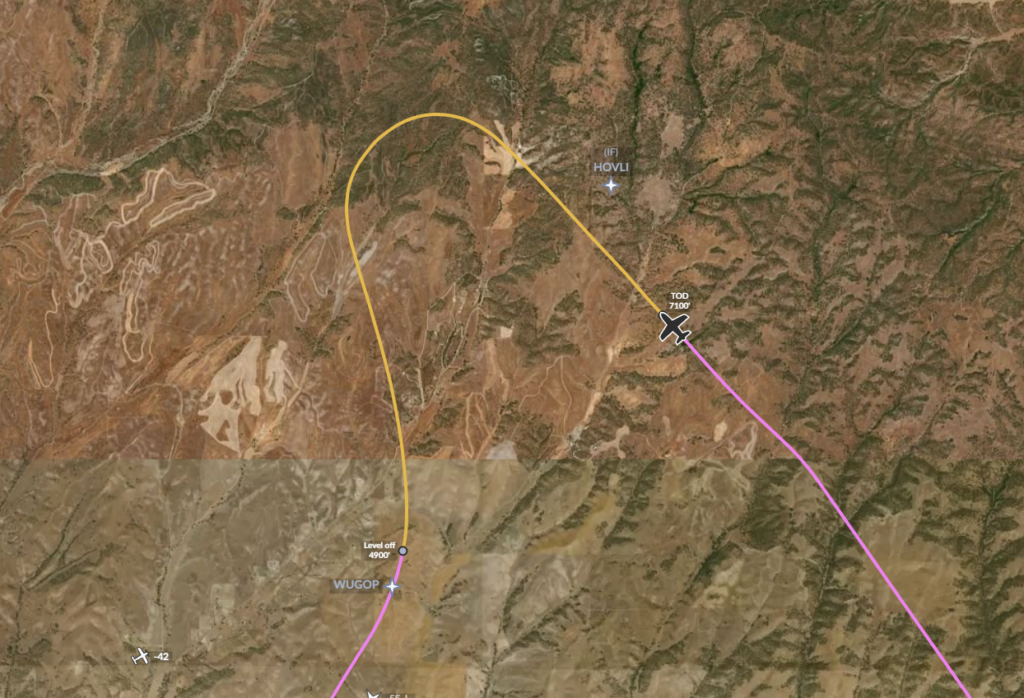

A Critical Mistake: Ignoring the Required Hold

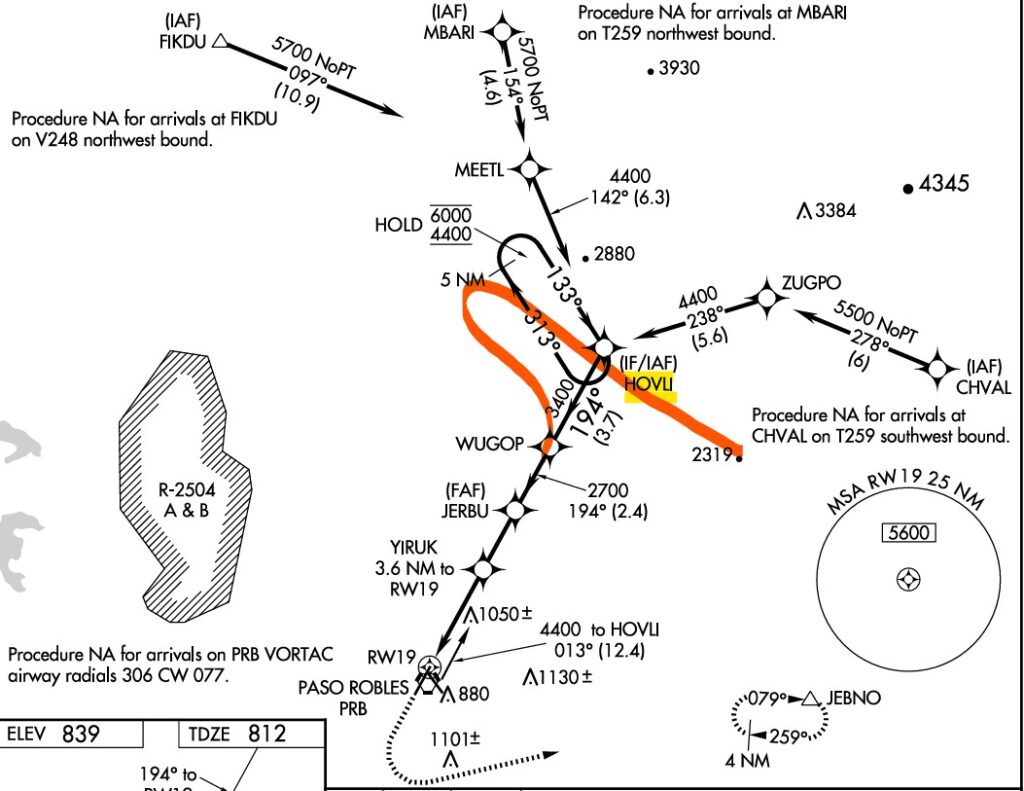

The Cirrus SR22T was cleared for the RNAV (GPS) Runway 19 approach at Paso Robles, beginning at the HOVLI initial fix (IF). However, because of the aircraft’s approach angle, the pilot was required to fly a hold at HOVLI before turning inbound on the approach.

🛑 What went wrong?

- The pilot did not properly enter the hold.

- Instead of taking the necessary time to descend in the hold, the aircraft remained too high and too fast.

- The approach became unstable, forcing the pilot to execute a go-around after reaching the runway threshold at excessive speed, that’s when things started to really fall apart.

for the RNAV (GPS) approach to RWY 19

The Unstable Go-Around and the Wrong Runway Alignment

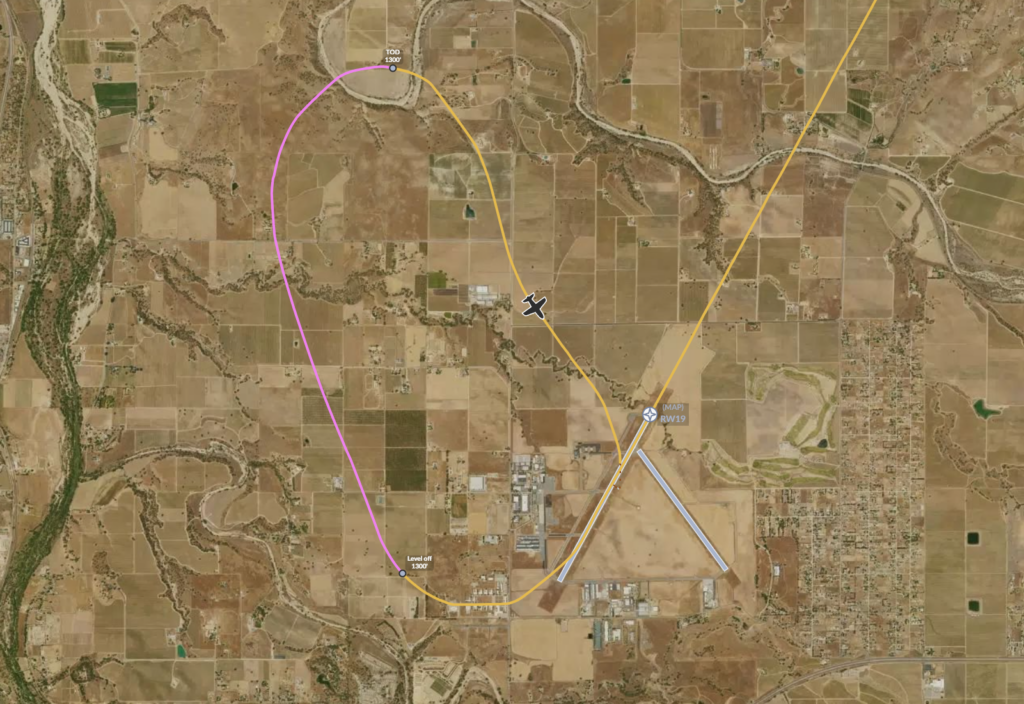

After the botched approach, the pilot initiated a go-around and requested a visual approach. However, this next approach was rushed and misaligned.

🔴 Key errors on the second approach:

- The pilots circled at an altitude no higher than 500 feet above ground level, most likely due to the weather with clouds at 800 feet

- Instead of properly circling for Runway 19, the aircraft mistakenly lined up for Runway 13.

- The heading bug on the aircraft was still set for Runway 19, meaning a simple cross-check could have prevented the misalignment.

- The aircraft was on a stable approach to the wrong runway at the correct speed.

At this point, the pilot had two choices:

✅ Land on Runway 13 without clearance

✅ Perform a second go-around

Unfortunately, the pilot chose a third, high-risk option: attempting a last-second turn at low altitude to realign with Runway 19.

The Final Moments: A Dangerous Low-Level Turn

At just 50 feet above the ground, the aircraft made a sharp turn to the right, away from Runway 13, but not enough to align with Runway 19. The aircraft crossed over Runway 19 but landed in the grass between the two runways, where it flipped over on impact.

Human Factors: Why Didn’t the Pilot Go Around?

Pilots are trained to go around when an approach is unstable, so why did this pilot try to “salvage” the landing?

🤔 Possible factors at play:

- Completion Bias – The desire to finish the approach after already going around once.

- Overconfidence – Believing they could “fix” the approach at the last second.

- Social Pressure – With passengers onboard, the pilot may have felt added pressure to land successfully.

- Decision Fatigue – After multiple high-stress events, decision-making may have been impaired.

Lessons for Pilots

This accident highlights key lessons that every pilot—especially those flying under IFR—should remember:

✈️ Always Fly the Required Hold – If an approach requires a hold, you must fly it. Skipping it can put you in a dangerous position.

✈️ Stabilized Approaches Are Non-Negotiable – If you’re too high, too fast, or misaligned, a go-around is the safest option.

✈️ Know When to Commit to a Go-Around – Trying to “fix” an unstable approach at low altitude is a recipe for disaster.

✈️ Cross-Check Your Heading and Runway Alignment – A simple heading bug check could have prevented the pilot from lining up with the wrong runway.

Final Thoughts

This was a survivable accident, but a preventable one. The pilot and passengers were lucky, but luck isn’t a safety strategy. The biggest takeaway? A go-around is always an option—never hesitate to use it.

14 Comments

This is inexcusable in a setting of having a CFI on the airplane. It doesn’t help that the CFI was a very low time serious pilot as well and probably did not understand the handling characteristics of that aircraft and thought she could coax it down like a Cessna 172. And I’m talking as a pilot with over 2000 hours in that aircraft. It makes me wonder how they see if eyes are trained nowadays. These are our potential 121 pilots in the future and that makes me concerned. I used to take CFI‘s up frequently in the cirrus into LAX and SFO etc. and I realize that even with 1000 hours the CFI many of them don’t have the skills to operate in such airspace and don’t have the quick thinking reflexes that you need.Hope those guys recover.

Awesome commentary… Totally agree with you 👍

Where was the flight instructor in all of this?

Yes… Unbelievable but yes.

Thank You Hoover..I appreciate

You’re welcome!

Thanks for the excellent summary. Again, my concern as Gone to Earth points out, is with the current CFI program. Professionalism, attention to detail and some basic flight skills seem to be left out of the syllabus for some.

KPRB is a non tower airport. You stated they were not cleared to land on Runway 13. They would have been cleared for the approach RNAV (GPS) Rwy 19. At some point they would have been cleared to contact CTAF. If not cleared they would have been asked to close their IFR flight plan once on the ground. In any event, landing at a non tower airport would not have necessitated their landing on 19. If lined up for 13, they simply could have announced on CTAF that they were landing on 13. I think a last minute try at 19 was not a wise choice. Of course their poor non stabilized approach to the airport was causal. And circling that low also wasn’t wise.

Thanks, let me go back and check the NTSB report and revise the blog.

In addition to my previous comment, why didn’t the pilot go to CHVAL fix for a NoPT option? They were coming from the Southeast and that would have made a lot of sense. This kind of NoPT segment is ideal for a fast airplane like the Cirrus, especially if you’re using the autopilot.

Not to bash the instructor, this situation should looked at as lesson learned. He may of have little time as instrument instructor. Any instructor should demonstrate any aspect of instruction in a professional mature. I have walked away from instructors who clearly do not demonstrate professionalism.

The article is a good debrief thanks. Especially, the decision fatigue comment.

What caught my eye was the direction of the turn after the initial go-around. Why would a pilot elect a right hand pattern to circle to land? The missed approach procedure is to the left to ensure avoiding the restricted area to the west and north. The plot of the track after the initial turn was a northwest track. Further, this is curious because their track paralleled the terminal route symbol used on the Jeppesen chart, which could indicate another misunderstanding of the procedure after having bypassed CHVAL intersection. Were they thinking Jeppesen’s depiction of the terminal route to be the missed approach procedure, and then spotted a runway (13) and decided to land. Subsequently realizing it was runway 13, shorter by a third the distance of runway 19 and deciding to make a last minute change that resulted in a low level accelerated stall.

Non pilot here…what does “flying the hold” mean?

It is an established predefined racetrack flight path to fly while waiting to proceed to point of intended landing. When required the pilot must follow this course. In this accident scenario the holding course would have giving the pilot an opportunity to get established on proper altitude and airspeed for the approach.