It was the day after Christmas, a calm North Texas evening with clear skies and a big, bright moon overhead. A Cirrus SR22, N858RC, was inbound to a small private strip near Canton, Texas—Thompson Field (1TA7). The pilot made standard calls in the pattern for runway 13: downwind, base, final. Everything sounded normal on the radio. But instead of touching down, the SR22 flew a path roughly parallel to the runway, about a few hundred feet east, and struck a tree line before impacting terrain near a house. The pilot did not survive.

Who Was at the Controls

The pilot held a private pilot certificate with airplane single-engine land and instrument ratings. He was 60 years old, not an occupational pilot, and flew recreationally under Part 91. His logbook totals were substantial for general aviation: about 1,273.5 hours total time and 1,230.7 hours as pilot in command. He had flown 51.1 hours in the last 90 days and 12.7 hours in the last 30. The report did not list hours in the specific make and model. His most recent medical was a Class 3 with limitations in December 2022, and his last flight review was in February 2022. Toxicology was negative for drugs of abuse, and no autopsy was performed.

Setting the Stage: Weather and Lighting

Weather was benign: VMC, winds roughly 170 at 5 knots, visibility 10 miles. Sunset had been at 1725, civil twilight ended at 1752, and the moon—a waning gibbous—rose at 1801 with 99% illumination. So while it was night, there was ample celestial light. But that didn’t make the runway easier to find or align with. Thompson Field is a private strip—2,500 feet long, 40 feet wide, asphalt, no instrument procedures. The runway edge “lighting” consisted of solar deck lights, some spaced around 140 feet apart, others wider than that. There were also similar lights used elsewhere on the property—at the ends of driveways and even on a picnic table by a refueling area. In short, not your standard, uniformly spaced runway environment, and certainly not something that guarantees runway-identifying cues on a dark night.

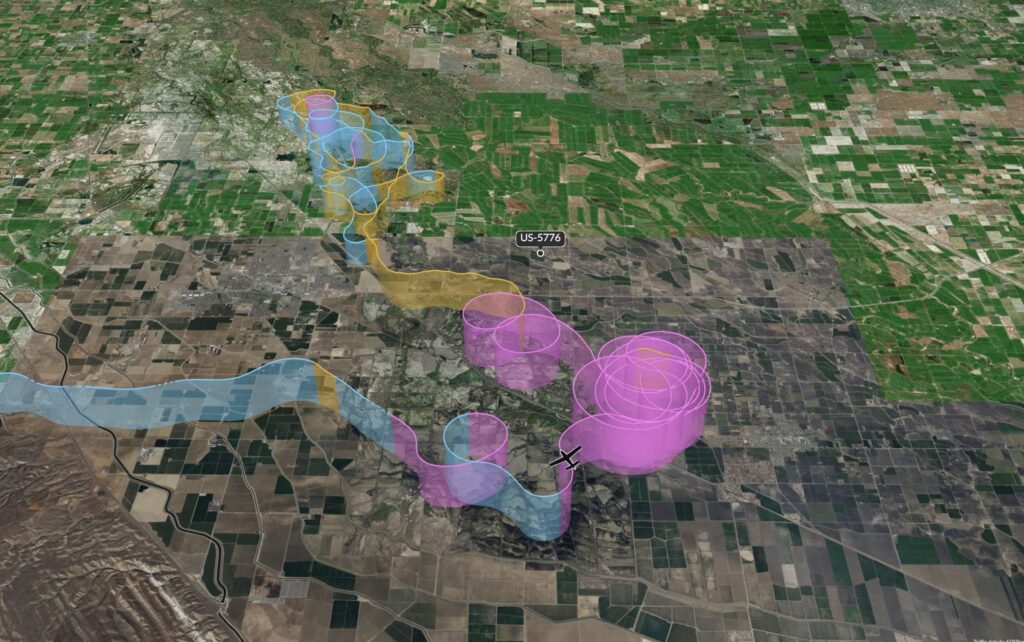

The Approach That Never Lined Up

What stood out in the non-volatile aircraft data was the ground track: on final, the airplane flew approximately parallel to runway 13 but about 340 feet east of the centerline before reaching the trees. That’s close enough to keep a pilot “committed” visually but far enough to miss the pavement entirely—especially if the lighting cues are unconventional. Importantly, the data showed minimal altimetry error and normal engine operation all the way through impact. Post-accident inspection found flight control continuity, the flaps at about 50%, and torsional damage on the propeller consistent with power at impact. No evidence suggested a mechanical failure or power loss. This looked like a visual approach problem, not an engine or instrument problem.

Human Factors: Why a Good Pilot Can Still Miss

The NTSB could not determine exactly why the pilot flew a parallel path east of the runway. With no autopsy, a sudden medical incapacitation could not be ruled out, but nothing in the record confirmed that. Toxicology was clean. Radio calls were normal. And with a bright moon, visibility should have been good. That leaves us with a familiar nighttime trap: expectation and illusion. Private strips with non-standard lighting can lure the eye to bright, isolated ground lights that “feel” like a runway environment when they’re not. Non-uniform spacing along the runway, plus similar lights scattered around the property, can shift a pilot’s mental picture just a few degrees off course. At 90 knots on short final, a few degrees is everything.

Micro-Terrain and the Last Few Seconds

The airplane struck a 40- to 50-foot tree line about 250 feet short of a house, and the wreckage path ran roughly 250 feet beyond that on a heading of 146 degrees. That is consistent with an airplane still flying, but not seeing or correcting for the lateral offset in time. Remember, the runway was only 40 feet wide. At night, with a narrow strip and ambiguous edge cues, lateral error can hide until the very end—especially if the pilot is stabilizing pitch and power and focusing primarily on descent rate and aiming point. When trees begin filling the windshield, it’s too late.

What the Board Concluded

The NTSB’s probable cause stated it succinctly: the pilot failed to attain the runway during a night landing, resulting in impact with trees. Darkness was cited as a contributing factor. Mechanical issues were not a factor, and the data supported that conclusion. This was a visual acquisition and alignment miss on a night pattern to a non-standard environment.

Lessons I’d Brief Before the Next Night VFR to a Private Strip

First, treat non-standard lighting like a non-precision approach with extra margin. If you haven’t landed there at night before—or it’s been a while—plan a deliberate setup:

- Build a lateral backstop. Load the runway centerline course into your GPS or moving map and verify you’re on it. If there’s a published runway extension or a user waypoint for the threshold, use it. Even a crude magenta line can save you from “parallel-final syndrome.”

- Stabilize early and far. Fly a wider, higher-than-daylight pattern so you have time to cross-check heading, track, and lateral deviation. Don’t be afraid to go around the first time just to survey the lighting picture.

- Brief the cues—and the false cues. If the “runway lights” are solar deck dots, know their spacing varies, and that other property lights may mimic them. Decide ahead of time what will confirm the runway (e.g., centerline alignment on the GPS and a continuous pair of edges) and what will not.

- Manage brightness and contrast. Dim the panel and maximize outside scan. On a bright-moon night, the ground can look washed out while the panel remains a magnet for your eyes.

- Have a go-around gate. If the centerline picture isn’t perfect by a specific altitude or distance—say, “if I’m not on the magenta and seeing two straight light lines by 500 AGL, I’m going around”—execute immediately.

Second, acknowledge how a narrow runway compresses your cues. Forty feet wide at night looks like a driveway in the dark, not a runway. That pushes you to chase vertical path and flare timing while ignoring lateral drift. Make lateral alignment an explicit callout—“centerline verified”—on short final.

Third, consider bringing IFR discipline to VFR nights, even in severe-clear conditions. Nothing prevented a GPS-guided straight-in to a waypoint aligned with the runway’s extended centerline, flown with vertical guidance from the autopilot in VS mode or a home-built “non-precision” profile. It’s still a visual landing, but you’re using the tools to remove ambiguity.

What About Fatigue or Currency?

The pilot’s recent flying suggested he was active—over 50 hours in the last 90 days and nearly 13 in the last 30. That argues against deep rust. But night currency is different from recent total hours. The file didn’t specify his night takeoffs and landings. Regardless, proficiency at night is perishable, especially to unfamiliar or private strips. Even experienced pilots benefit from a daylight recon before a night arrival to a non-standard runway, or from planning a bright-line “no-go” if the lighting doesn’t meet expectations on arrival.

Final Take

When we boil this accident down, it wasn’t weather, and it wasn’t the engine. It was geometry and perception—mis-identifying or mis-aligning with the runway environment on a dark night where the lights didn’t behave like airport lights. The airplane tracked a few hundred feet east of the runway, stayed on that line, and ran out of space. The guardrails we can add—GPS centerline, disciplined gates, planned go-arounds, and a skeptical eye toward “runway-ish” lights—are all available to every GA pilot. This one reminded us that on night VFR, your best friends are margins and tools, not assumptions.

2 Comments

Good Debrief. Non-standard and standard lighting can be a real problem. Had a student try to join up on a lighted gas station one night. Take away your reference points and things can go south in a hurry. Good points for all to apply.

The best idea might be as Hoover said, use it as instrument landing practice. Wouldn’t you think though, that a private owner with trees near the runway, would either chop them down or put lights on them?