On a clear autumn evening in October 2023, a highly experienced pilot lifted off from a small California airstrip with a single passenger onboard. What should have been a routine leg of a cross-country journey ended tragically just moments after takeoff. Today, we unpack the chain of decisions, environmental factors, and split-second dynamics that led to the fatal crash of a Beechcraft A36 Bonanza in Covelo—and the critical safety takeaways every pilot should carry forward.

A Veteran Pilot in Command

The man at the controls that day wasn’t a novice. At 54 years old, he held an airline transport pilot certificate and a first-class medical with no limitations. With over 20,000 total flight hours, his résumé reflected the experience of a seasoned professional. He was rated for both single-engine and multi-engine aircraft and was employed as a professional pilot. Yet even with those credentials, the accident underscores a sobering truth: aviation doesn’t discriminate when it comes to risk.

The Flight Plan: From Utah to the Coast

Departing from Heber City, Utah, the pilot and passenger set out on a personal flight under Part 91 regulations, destined for Shelter Cove on California’s rugged northern coast. After a 4-hour, 11-minute flight, the aircraft reached the vicinity of Shelter Cove—but instead of descending, it veered inland.

Why the detour? Satellite imagery later confirmed coastal cloud cover at the destination, likely prompting the pilot to divert. He touched down instead at Round Valley Airport (O09) in Covelo, topping off with about 90 gallons of fuel before preparing for another departure.

The Airport and the Environment

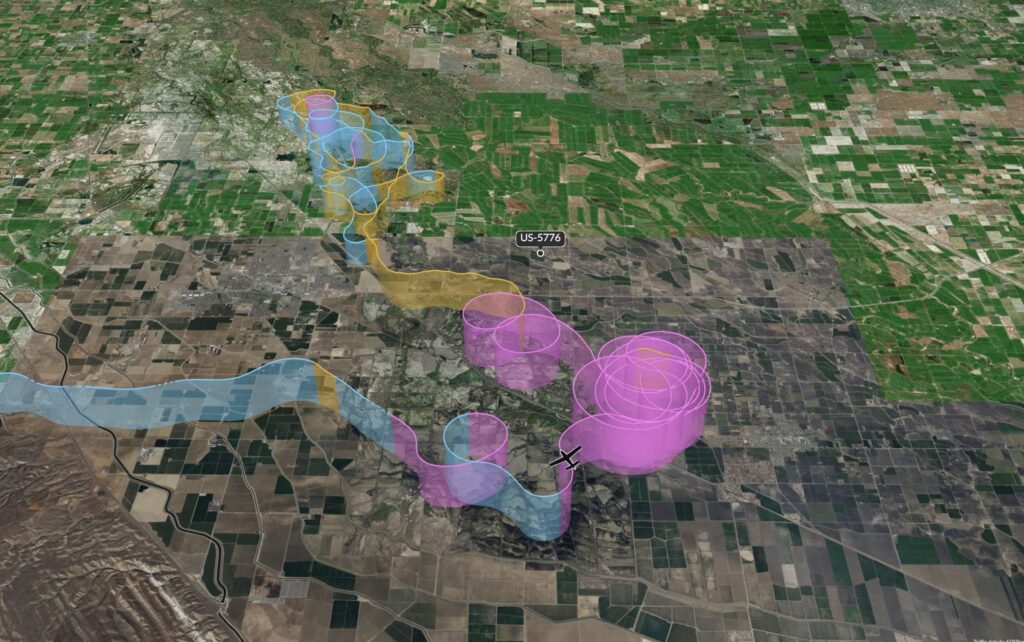

Round Valley is a small airport tucked amid steep hills and mountains. At 1,434 feet elevation, it offers two runways—10 and 28—each 3,670 feet long. The surrounding terrain, however, tells a different story. Off the end of runway 28, the direction chosen for takeoff, the land rises sharply with peaks and valleys and a 4,000-foot mountain just a mile away.

To make matters worse, FAA chart supplements failed to adequately describe the dangerous terrain immediately west of the runway—information that could have played a crucial role in the pilot’s decision-making.

Takeoff and the Fatal Turn

At approximately 6:01 p.m., with no flight plan filed and skies reportedly clear, the Bonanza lifted off runway 28. According to one witness, it was already near the departure end of the runway before becoming airborne. He and his children waved at the pilot, who waved back—a hauntingly personal detail in the minutes before disaster.

A second witness described the aircraft clearing a group of trees by about 20 feet, then entering a steep left turn with a bank angle of 70–80 degrees at just 60 feet above ground level. The aircraft quickly lost altitude and slammed into a hillside, erupting into flames.

What prompted such an aggressive turn? The NTSB couldn’t determine the precise reason. It’s possible the pilot was trying to maneuver away from terrain or react to a perceived engine issue—one witness did hear a brief “popping” sound. Still, engine and airframe analysis showed no mechanical anomalies.

Performance Pressures

Performance data paints a telling picture. The aircraft, equipped with wingtip fuel tanks and heavily loaded, was close to its maximum takeoff weight of 3,833 lbs. Given the density altitude of over 3,200 feet and a tailwind component of 1 knot, the plane needed at least 2,625 feet of ground roll to take off safely. That left little room for error if the pilot started the takeoff from the fuel-pump-adjacent taxiway, which offered only 2,400 feet of available runway.

What’s more, the climb rate was reduced due to the aircraft’s weight. The STC (supplemental type certificate) called for a 100 fpm reduction in climb performance above 3,650 lbs, making terrain avoidance even more difficult after takeoff from runway 28.

Stall Speeds and Turning Limits

The aircraft’s stall speed under its configuration at the time—flaps up and heavily loaded—was about 64.5 knots indicated airspeed (KIAS). With an 80° bank angle, the stall speed would have climbed significantly. In fact, witnesses said the airplane appeared to be flying near stall speed (around 84 KIAS) while banked at a steep angle, potentially flirting with aerodynamic stall margins.

However, based on the angle of descent and the impact pattern, the NTSB concluded the crash was more consistent with controlled flight into terrain (CFIT) than a stall/spin. The pilot appeared to still be in control—but simply couldn’t outclimb or out-turn the rising terrain.

Decisions, Not Distractions

One decision stands out more than any other: the choice to depart on runway 28 rather than 10. Local pilots and residents noted that most aircraft typically take off to the east (runway 10), where flat farmland stretches for miles, offering ample escape routes in case of engine trouble. In contrast, runway 28 points almost immediately toward rising hills and that infamous 4,000-foot peak.

It’s worth noting that the FAA’s chart supplement lacked any detailed warning about this treacherous terrain—an omission cited as a contributing factor in the accident.

Final Thoughts: Lessons from Covelo

This accident is not the result of one glaring mistake but a confluence of subtle risks: challenging terrain, a possibly short-field takeoff, heavy weight, modest tailwind, and an unexplained steep turn just after liftoff. Any one of these could be manageable in isolation—but together, they proved fatal.

For pilots, the lessons are sobering yet clear:

- Respect the terrain. Even familiar airports can conceal deadly surprises, especially when chart supplements fall short.

- Weight and performance margins matter. Being “within limits” doesn’t guarantee ample safety cushion.

- Consider takeoff direction carefully. Especially at mountain-surrounded airports, the direction you choose can be the most critical decision of the flight.

- Beware steep low-altitude turns. Especially when close to stall speed and with terrain looming ahead.

With over 20,000 hours in his logbook, the pilot was undoubtedly a competent aviator. But aviation is an unforgiving profession, and as this tragedy in Covelo reminds us, even the most experienced among us are only as safe as our last decision.

9 Comments

Love these debriefs.

So do I.

Just curious

If it was daylight and clear weather was the higher terrain visible from cockpit when take off roll started

I agree; I’ve just started reading these debriefs, having watched the video debriefs for quite some time. Hoover, you do an excellent job and service to the community.

Superbly written and analyzed.

The descriptive details create a chilling, disturbing, and haunting account, some conditions of which may be, in the end, inescapable as they lie just outside the boundaries of all human intellect. Given this pilot’s impressive flying background and experience, one wonders if, perhaps, the hand of Dame Fortune or Fate supersedes the intellect’s capacity to control and manage events in the external world as they unfold into the Present.

Just idle speculation. Nothing more.

Except to say, I would not miss a Pilot Debrief for the world.

All things considered why did the pilot take off with so much fuel? One has to wonder if this would have ended differently if his fuel load was less, ?? My condolences to the families, thank you Hoover for this pilot debrief .

Yes, I don’t understand why the takeoff couldn’t have occurred to the SE on runway 10 over flatter terrain, especially when the winds (even as low as 1Kt) were out of the SE heading NW; just would have helped a little for lift. The lay of the land (for an unfamiliar airport) seems to beg for a runway 10 takeoff. What a tragedy.

This pilot was my Father. Since his passing I’ve gotten into aviation myself. Hopefully about to pass my PPL check ride! I am still confused as to why he took off the runway he did. I come to these forums every once in a while to see what others think. Personally, I think he had a case of “get-there-itis.” But who knows. I’m just a measly student pilot! Thanks all for keeping it respectful for those we lost.

I’m sorry for your loss but I’m glad you are pursuing aviation and wish you the best on the journey. Good luck on your PPL!