A Thanksgiving Journey Turns Tragic

On the Saturday after Thanksgiving 2023, a family of three departed Las Cruces, New Mexico, for what was supposed to be a routine cross-country flight home to San Antonio, Texas. Their aircraft: a 1964 Piper PA-28-180 Cherokee. Their pilot: a 36-year-old husband and father with a private pilot certificate, around 94.7 total flight hours—all in the same make and model—and no instrument rating. Accompanying him were his wife and 10-year-old daughter.

Their destination was Bulverde Airpark. But tragically, they never made it. Instead, their aircraft crashed into hilly terrain near Mertzon, Texas, killing all three aboard.

The Pilot’s Background

The pilot was relatively new to aviation. With just 94.7 hours total time, all in the Piper Cherokee, he had also logged only 4.5 hours at night and 3.1 hours of simulated instrument flight. He had passed a flight review just six weeks prior, on October 10, 2023, and had a valid third-class medical certificate from earlier that year. However, he did not hold an instrument rating and lacked the kind of experience needed to safely navigate deteriorating weather or nighttime conditions.

Planning a VFR Flight Through Questionable Skies

The plan filed with the FAA was for a visual flight rules (VFR) flight from Las Cruces (LRU) to Bulverde Airpark (1T8), a route that would take them across parts of western Texas. The filed altitude was 10,500 feet, but weather briefings warned of marginal VFR and multiple AIRMETs predicting IFR (instrument flight rules) conditions, including overcast layers below 3,000 feet AGL.

Despite this, the pilot appeared confident the trip could proceed. His father later recalled the pilot saying it was just “a little cloudy.” But clouds, especially at night, can hide serious hazards—and for a pilot with no instrument training, they are a deadly trap.

Deviation After Deviation

The flight began around 10:00 AM MST. ADS-B data shows the aircraft climbed to 9,700 feet, but only briefly. About 25 nautical miles east of Las Cruces, the descent began. The aircraft flew between 7,700 and 7,300 feet until it reached its first fuel stop at Pecos Municipal Airport (PEQ) around 12:25 PM CST, where 14.5 gallons of 100LL fuel were added.

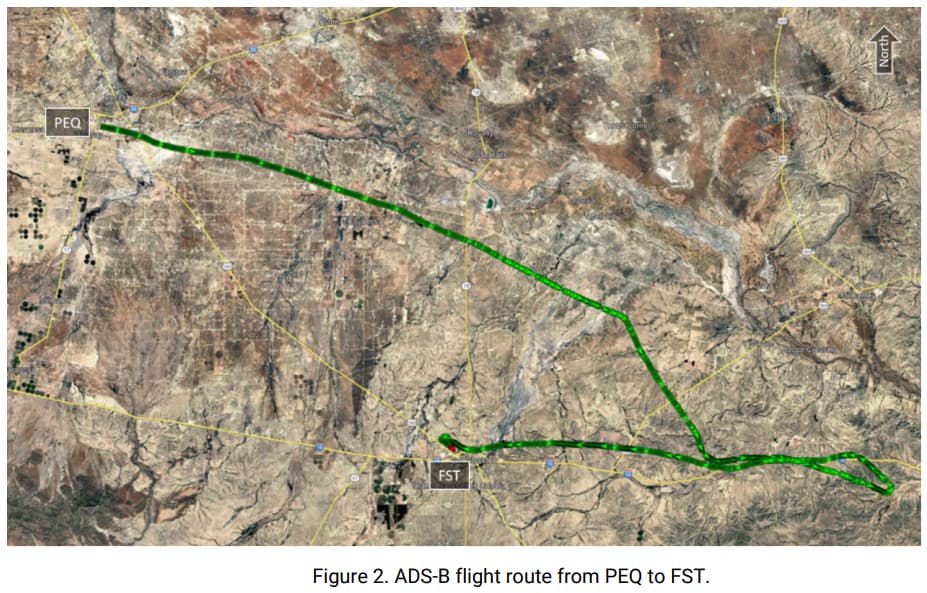

After departing PEQ around 12:52 PM, the aircraft aimed for its destination—but then came trouble. About 27 minutes into the second leg, the pilot began deviating from his heading. The altitude dropped again, down to 3,100 feet at times. Then, the aircraft turned back west, heading nearly 40 miles off course to Fort Stockton (FST).

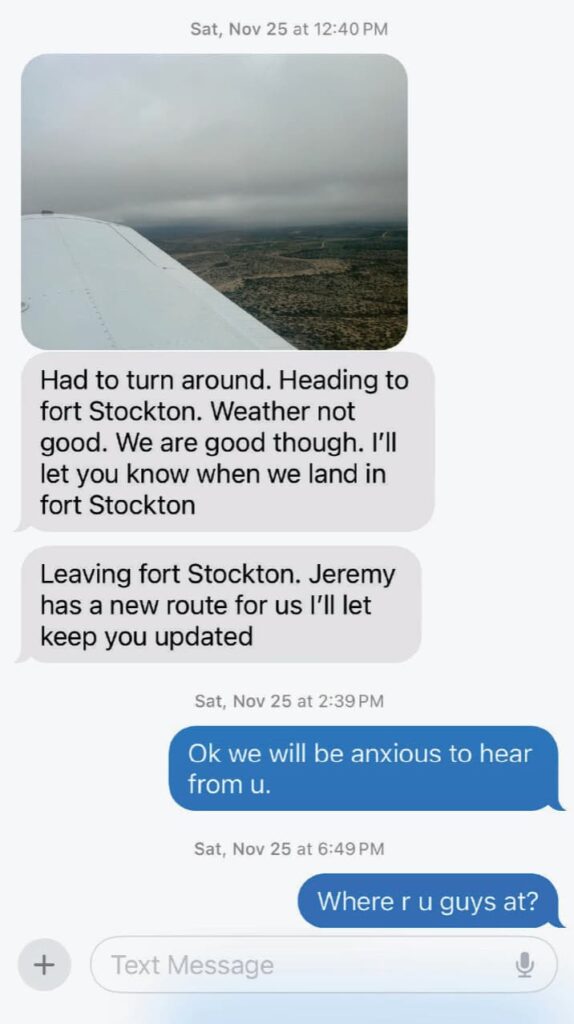

Why the turnback? A chilling clue came via text message. The pilot’s wife sent a photo to the pilot’s mother. The image showed the aircraft beneath low clouds, flying in visible moisture. The message was simple and stark: “We had to turn back—the weather was not good.”

Pushing Forward Despite Warnings

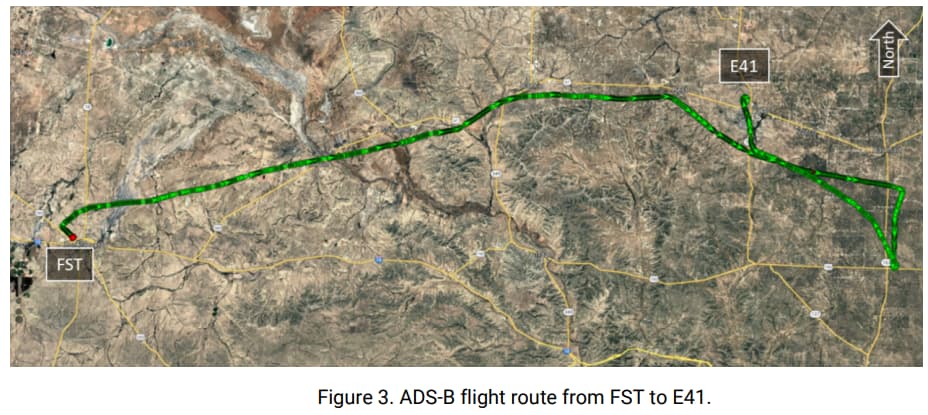

At FST, the family paused. But only briefly. They took off again at 2:31 PM, now flying east-southeast toward their new stop: Reagan County Airport (E41) in Big Lake, Texas. ADS-B data showed low-level maneuvering again, with the aircraft mostly flying around 3,500 feet. They arrived at 3:40 PM and added 24.39 gallons of fuel.

Then came a curious delay. For reasons unknown, they remained at E41 for over 2.5 hours. It was now after sunset, and night had fallen.

Still, the pilot took off again—into darkness, beneath overcast ceilings as low as 1,100 feet, in non-VFR conditions.

Final Moments: A Deadly Descent

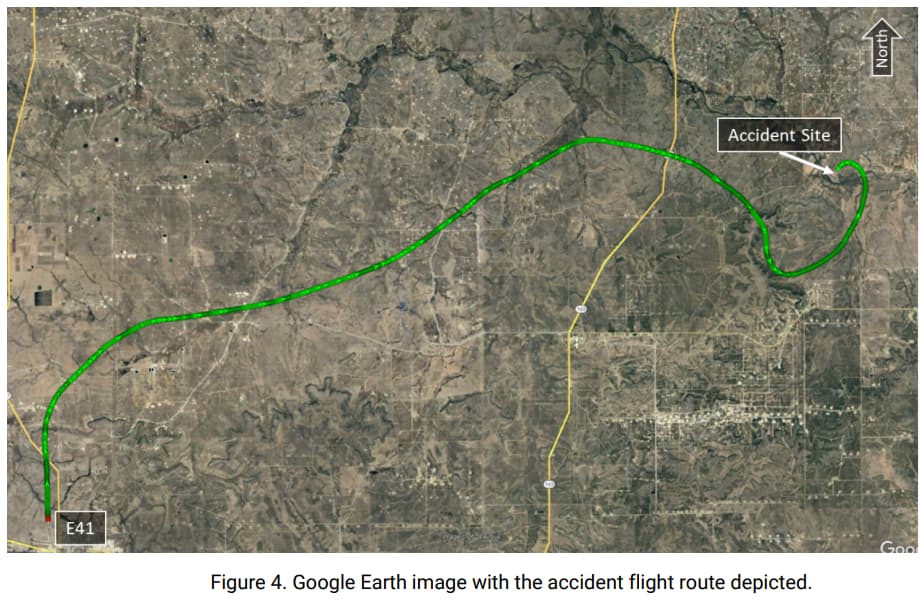

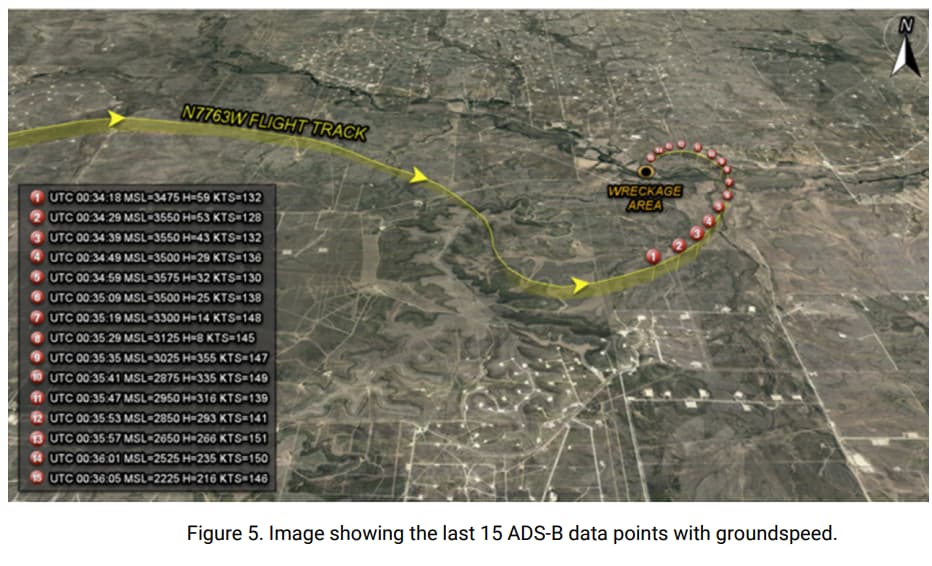

The Cherokee lifted off from E41 around 6:18 PM. For the next few minutes, it flew between 3,900 and 3,000 feet, making several heading changes, perhaps attempting to navigate visually in near-IMC conditions. The terrain in this region of Texas is hilly, and the combination of low ceilings, darkness, and a lack of visual references proved fatal.

At 6:35 PM, the aircraft began a shallow left turn. It accelerated and descended. In the last four seconds, the turn tightened. The aircraft struck a small tree and impacted the ground in a high-energy, low-angle crash, scattering debris over 186 feet.

All three occupants died on impact.

The Aftermath and NTSB Findings

There was no mechanical failure found. The aircraft had been maintained, and its engine was working. The probable cause, according to the NTSB, was:

“The non-instrument-rated pilot’s continued visual flight into night instrument meteorological conditions, which resulted in spatial disorientation and subsequent loss of control. Contributing to the accident was the pilot’s overconfidence.”

In simpler terms: he got lost in the clouds and didn’t know how to fly the airplane solely by instruments. He was flying by feel—an impossible task in the dark and under the clouds.

Spatial Disorientation: A Hidden Killer

Spatial disorientation occurs when a pilot’s senses trick them into believing the airplane is in a different attitude than it really is. It’s most common in conditions where there are no visual references—such as in clouds, fog, or darkness. According to FAA guidance:

“Unless a pilot has many hours of training in instrument flight, flight should be avoided in reduced visibility or at night when the horizon is not visible.”

Without the ability to rely solely on instruments—and without the experience to trust them—many pilots unknowingly fly themselves into a dive, a bank, or even an inverted position.

That appears to be what happened here.

Lessons from a Preventable Tragedy

- Respect the weather. Marginal VFR and IFR forecasts aren’t just technical warnings—they are red flags that VFR-only pilots must heed. The pilot had clear signs that conditions would be challenging, even before departure.

- Get the rating—or know your limits. An instrument rating isn’t just a piece of paper. It equips pilots to handle clouds, visibility loss, and the sensory confusion that comes with spatial disorientation.

- Night flying isn’t just VFR in the dark. It’s a different ballgame altogether. Terrain awareness, lighting illusions, and lack of horizon cues can disorient even seasoned pilots.

- Don’t press ahead because you feel lucky. The pilot here likely believed he could “thread the needle” between weather bands or just “stay low.” But that strategy only works until it doesn’t. This flight was changed multiple times, turned back once, and delayed—yet still continued after dark.

- Passenger pressure can be silent but powerful. Though not directly mentioned in the report, flying with family on a holiday weekend may have added a layer of emotional commitment to “getting home.” It’s a trap many pilots know well.

Conclusion

This was a heartbreaking accident that highlights the intersection of overconfidence, inexperience, and poor weather decision-making. A family of three perished not because of mechanical failure or sabotage—but because of a decision to fly when they should have waited or stopped altogether.

There’s no shame in canceling or delaying a flight. But there is great danger in pushing forward when the conditions don’t support the capabilities of the pilot or the aircraft.

3 Comments

This is another great PD. I love these PDedriefs.i actually like to read them it out loud. I always think of “what they could have done” instead of taking that flight. Hoover ,in all of your videos and website articles ,I wait to hear or read the ” cause and soultion” of accident. I personally would like to see all ore 2020 airplanes banned from flying. Only new airplanes equipped with the latest technology *software , hardware and satellite technology should be allowed to fly . Along with A.i . Hoover you have a great youtube channel and website . Everything is hear and airplane flying above my house ,I think of the piolet,year of the plane and you.

Perhaps we need more seminars for family members to educate them about potential flying hazards and weather related traps that idiot pilots fall prey to resulting in fatalities for everyone….ugh

I can’t be help thinking that if you have a family that’s flown with you routinely, they can dramatically contribute to ‘get-there-itis’. The family, not being pilot qualified, don’t have an appreciation of the potential difficulties and skills required for IMC and night flying. Also, one can see normal conflicts arising in the plane over other family matters with bickering and arguments, tremendously adding to the difficulties of the pilot now forced into the role of mediator, while being the PIC. I have no doubt this was a factor in JFK Jr. crash. There was tension over being late and its easy to see the ladies in back getting into an argument, tremendously distracting JFK. As an aside, I lived in the Texas hill country this flight was over and those Caliche hills, are numerous and rise up steeply in the terrain. The rock itself (Caliche) is a stark, off-white color that can easily be ‘disguised’ in all but the most clear weather.