This one started as a simple Saturday hop: Aero Country (T31) up to Sherman Municipal (SWI) in a well-worn Piper PA-30 Twin Comanche. Weather was cooperative—clear skies, 10 miles of visibility, and a 12-knot breeze out of 210°. Nothing about the setup suggested trouble. But about 40 minutes later, the airplane was nose-down in a field east of Sherman, the pilot fatally injured, and a long chain of small factors had stacked up into a big outcome.

The Pilot and the Airplane

The pilot was a 69-year-old private pilot with single- and multi-engine land ratings and an instrument rating. He held a third-class medical with limitations issued just three days earlier. His logbook showed about 540 total hours, with a substantial 376 hours in the PA-30—so not a newcomer to the type. Recent experience was thin: roughly 3 hours in the last 90 days, and none in the last 30 days or last 24 hours. That matters in a twin, where proficiency is perishable, especially around engine-out procedures and habit patterns. The airplane itself was a 1969 Twin Comanche, 3,641 hours on the airframe at last inspection, and 24 hours since its annual in November 2022. Two Lycoming IO-320s up front and a fuel system with mains, aux tanks, and wingtip tanks plumbed into the auxes. Fuel selection in this model is flexible—but that flexibility introduces opportunities for mis-selection.

The Flight: From Routine to Head-Scratcher

ADS-B shows the Twin Comanche departed T31 at 09:02, climbed to about 5,000 feet MSL, and cruised north toward Sherman. At 09:19:20, onboard data recorded the first red flag: the right engine’s fuel flow fluctuated for about 15 seconds. Roughly 35 seconds later, the left engine’s fuel flow dropped to zero, along with falling CHTs and EGTs—classic signs of fuel starvation or interruption. From about six miles southeast of SWI, the airplane started a shallow right orbit, then drifted east—away from the destination—on a gentle descent. Around 09:26, the left engine’s fuel flow briefly surged, then fell back to zero for the remainder of the flight. The pilot eventually turned west toward the airport, still descending. By 09:41, ADS-B had the airplane less than 100 feet AGL, groundspeed around 61 knots, and a left turn of about 40° in the last four seconds before impact. That combination—low altitude, low energy, and a turn—left no margin.

What the Wreckage Said

The airplane impacted a field on a southwest heading and slid to a stop upright. Both props were in soft dirt with minimal rotational scoring, and all blades were near the low-pitch stop—not feathered. The gear and flaps were retracted, consistent with a forced landing effort that never fully materialized. Investigators sampled the tanks: roughly 9 gallons in the left main, 11 in the left aux, 9 in the right main, and 3 in the right aux. No fuel recovered from either tip tank. Both electric fuel pumps were found switched on. The left fuel selector handle was found in OFF; the right was on MAIN. That left-side OFF position is the kind of detail that changes a survivable engine-out scenario into a high-drag descent, especially if the propeller isn’t feathered.

On the right side, maintenance findings told another story. The right fuel selector showed rust and water contamination partially blocking the filter elements. Low-pressure bench tests indicated partial blockage to the right aux port, and, more troubling, air leaked through the aux port even when the handle was at OFF or MAIN—classic internal corrosion and wear. The handle itself was stiff and produced grinding when turned. On the engines, both crankshafts turned freely with normal compression; magnetos sparked at all posts. The left fuel servo screen was clean; the right had rust particles but wasn’t blocked. In short: the right side had a sick fuel selector, and the left side was shut off.

The Gotcha: Opposite Selector Motion

A small but critical Twin Comanche quirk sits right on page five of the report: the diagram of the left and right fuel selectors shows that the two handles rotate in opposite directions for the same selections. It’s one of those design choices you learn early in type training and then file away—until workload spikes. If you reach to move the “other” selector quickly, habit can betray you. The NTSB notes it’s possible the pilot, intending to move the right selector from AUX to MAIN, inadvertently moved the left selector from AUX to OFF. That hypothesis lines up with the data: the right engine’s fuel flow first wobbled (consistent with a corroded, partially obstructed selector), and then the left engine went to zero fuel flow. The human-factors lesson lands hard here—mirror-image controls that move opposite directions are a trap when stress levels rise.

Energy, VMC, and the No-Feather Problem

The left propeller was not feathered at the accident site, and the right wasn’t either. In twins like the PA-30, a windmilling prop can be a massive drag device. That drag raises VMC, the minimum controllable airspeed with one engine inoperative, and it erases glide performance quickly. Down low, without feather, the only way to keep control is to keep the airspeed up and minimize turns. Instead, the airplane ended up at about 61 knots groundspeed and made a left turn near the ground. Whether one engine was still producing partial power is academic at that point; the energy state just wasn’t there. The NTSB’s probable cause hits that directly: a loss of control during a forced landing following loss of engine power, with failure to feather the left prop called out as a contributing factor.

Human Factors: Medications and Margin

Toxicology found diphenhydramine in cavity blood at 70 ng/mL and in urine. That’s the sedating antihistamine many of us know as Benadryl, and the FAA’s guidance is blunt: do not fly within 60 hours of taking it due to impairment risk. The report also detected tadalafil, tamsulosin, yohimbine, and acetaminophen. Importantly, the NTSB couldn’t determine whether any medication effects were present or significant at the time of flight, and postmortem redistribution makes the numbers hard to interpret. Still, when you’re managing a complex abnormal—fuel system troubleshooting in a twin, at low altitude—any subtle cognitive slowing, even just fatigue or rustiness, can tip the scales. Combine that with limited recent flight time and a right-side mechanical issue that demanded calm, methodical action, and the margin narrows.

Decision Points and Missed Opportunities

A few branches in the decision tree stand out. First, the airplane was within gliding range of options early in the event. After the initial fuel-flow anomalies, the track shows a drift away from SWI on a shallow descent for several minutes. That time could have been converted into a straight-in or a high-key/low-key setup to any suitable runway or even a big field picked early. Second, fuel management and selector verification are checklist items for a reason—on this airplane, each selector’s position should be verbally and visually confirmed, especially because left and right move opposite. Third, prop feathering. In training we say “identify, verify, feather,” and then we back it up with the checklist. Here, neither prop was feathered. It’s possible the pilot was troubleshooting for a restart, or uncertain which side was reliable, or working the problem late in the descent. But once you commit to a power-off landing, the priority is maintaining control and airspeed, and that means drag reduction and a shallow, wings-level approach as long as possible.

What We Can Take to the Hangar

A few crisp lessons to brief before your next twin flight:

• Know the quirks of your fuel selectors cold. In the PA-30, left and right rotate opposite directions. Physically touch, point, and verbalize before you move either handle. If you’re moving one, look at both.

• Treat any unexplained fuel-flow fluctuation as time-critical. Turn toward an airport immediately, trade altitude for options, and get configured for a no-power landing while you troubleshoot.

• When an engine quits low, energy is king. If feathering is part of your emergency profile, do it decisively—drag from a windmilling prop will eat your glide. Maintain airspeed above VMC and avoid steep turns, especially close to the ground.

• Medication rules aren’t bureaucratic trivia. Even over-the-counter sedating antihistamines can dull your edge. If there’s any doubt, sit it out.

• Recent experience matters. If your last multi-engine reps are months old, go fly with an instructor for engine-out drills and fuel-system flows. Muscle memory is what keeps you from twisting the wrong handle when the pressure spikes.

The NTSB didn’t assign blame here, but the probable cause and findings sketch a clear picture: a mechanical issue on the right side, a likely inadvertent selector move shutting off the left side, no feather on the left prop, and a low-energy turn to impact. It’s a string of small misses in an airplane that demands precision when things get weird. Reviewing the selector diagram on page five and walking through those flows in the cockpit might be the 10-minute habit that keeps a small anomaly from turning into a forced landing you can’t control.

Bottom Line

This was a manageable abnormal that became unrecoverable at low altitude. The airplane told us plenty: right-side fuel-selector corrosion and contamination, the left selector found OFF, both props unfeathered, fuel in all four main/aux cells, and good weather. The human story is familiar—limited recent time, potential medication effects, and cockpit complexity under stress. The fix for the rest of us is straightforward: brief the quirks, practice the flows, and keep your energy high until you’re lined up with something you can land on.

3 Comments

Hoover..l love these weekly reports . Although I no longer fly, your writings brings me right back into the cockpit. Thanks!

All detailed reports are meticulously prepared and easily understood. I offer an additional comment as well.

Compared with many publications these days, it is pleasing to read perfect grammar and spelling. This fact aligns with your obvious high level of professionalism in aviation.

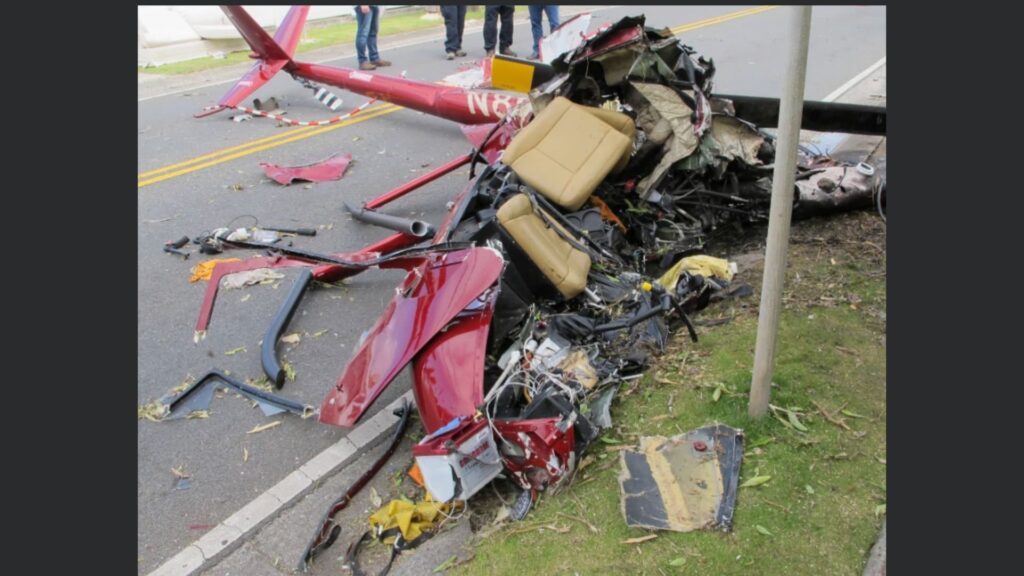

I met the ABC (Australia) chopper pilot a couple of times in my sailing days and I know that even with an abundance of experience, accidents can and will happen in a three dimensional profession. What happened in his case was very sad, and as you state, these reports are authored for a very valid reason…to be read. Date of crash

Thank you Hoover. Keep well.

Sorry: Date of chopper crash I referred to was 18Nov2011.