Into the Valley: How a Circling Approach Claimed Two Lives

Anh was 33, and flying had become her passion. She started out as a flight attendant, but her heart was always in the cockpit. Through persistence, late nights, and no shortage of hurdles—including a failed checkride and financial sacrifice—she made it. By late 2016, she had landed her first job as a professional pilot, hired by Air Cargo Carriers (ACC) to fly the Shorts SD3-30—a boxy, rugged turboprop converted for hauling cargo.

By the time of the accident in May 2017, Anh had logged about 650 hours of total flight time. Roughly half of that had been spent in the right seat of the SD3-30. She was green, sure—but she was growing, gaining experience, and doing what she loved. She’d only been with the company for six months, and everything was still new. She had no way of knowing she wouldn’t see month seven.

The Captain

Anh’s flying partner—because that’s how ACC did it, pairing pilots essentially full-time—was a 47-year-old captain with over 4,300 hours. More than 1,000 of those were in the SD3-30, including nearly 600 as pilot-in-command.

His resume looked solid on the surface. But it only told part of the story.

Dig a little deeper, and you’d find a history of checkride failures—four of them, in fact. Private, commercial multi-engine, single-engine flight instructor, and even the checkride to become a captain at ACC. He also failed to complete training at a prior employer and was fired from another for an incident involving a hangar door.

When he applied to ACC, he claimed he’d never failed a checkride. He wasn’t telling the truth.

ACC didn’t catch it—not because they didn’t care, but because there was no system in place to catch it. There was no formal background check beyond what the Pilot Records Improvement Act required, and PRIA didn’t show the failures. It was a box checked, not a deep look. He made it through.

The Pairing Problem

Anh and her Captain were based out of Charleston, West Virginia, and as far as ACC was concerned, they were now a permanent team. That’s how the company did things—one base, one crew. The only way out was to switch bases or get reassigned by the company.

There was no line flying with multiple captains. No mentorship. No opportunities to learn different cockpit cultures. Just the two of them, flight after flight.

In combat aviation, permanent pairings can work—under very specific conditions. But in the Part 135 cargo world? It’s risky. Without oversight, permanent pairings can drift into bad habits. Complacency creeps in. Procedures soften. And if something isn’t working? You’re stuck.

Anh was stuck.

The Red Flags Start Early

Two weeks into the job, Anh texted a friend in panic: “Just had the biggest scare of my life. Thought I was going to die.” After takeoff, a gear indication didn’t extinguish. The Captain, uncomfortable in instrument conditions, started making steep 60-degree banked turns through clouds, trying to descend back under the weather. Disoriented, low, and nearly trapped by terrain, they eventually broke out and landed—wrong direction on the runway.

Anh didn’t report it to the company. She was new, unsure, and—understandably—afraid of rocking the boat.

More texts followed. “Captain is sleeping… I’m gonna need you to keep me entertained for the rest of the flight.” She was flying solo, with no autopilot, while her Captain napped beside her. At first, she brushed it off. Then it became a pattern.

“He’s lazy… asks me to fly all the time… depressed about his girlfriend… I’ve been flying the whole week.”

Even worse: he avoided flying in clouds. He was a bush pilot from Alaska, used to VFR. IFR made him nervous. “His IFR flying is not great,” Anh wrote.

By March 31st, a month before the crash, they flew a flight at 4,000 feet to stay under the clouds—scud running through West Virginia hills. It was a last-ditch technique used when pilots didn’t trust themselves in real IMC.

Anh knew it wasn’t right. But she didn’t know what to do.

An Airline Without a Safety Net

ACC had no formal safety reporting system. No Initial Operating Experience (IOE) program. No structured feedback. The only way to voice concerns was to call or email the Chief Pilot directly—something few rookies would feel comfortable doing.

The company assumed no news meant good news. But silence isn’t always consent. And in this case, it was a warning unheard.

The Flight

May 5, 2017. Flight 1260 departed Louisville before sunrise. Anh and her Captain were headed home to Charleston. Just a short hop. The Shorts SD3-30 climbed to 9,000 feet. Everything seemed routine.

They called up the ATIS near Charleston. Weather reported broken clouds at 1,300 feet. Legal for a non-precision approach. But the ATIS was outdated. A special weather observation had come out seven minutes earlier: now the clouds were overcast at 500 feet, with fog down in the valleys.

The tower never updated the broadcast. Worse, when the crew checked in, the controller didn’t mention the new weather.

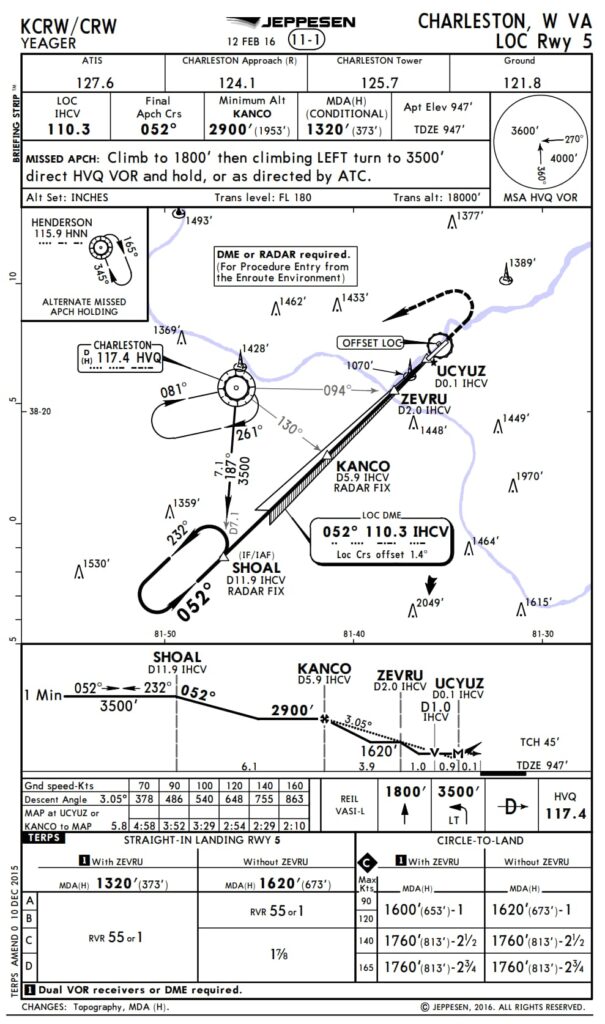

He told them to expect the localizer approach to Runway 5. It was the better option—a straight-in approach with descent minimums that might have gotten them safely below the clouds.

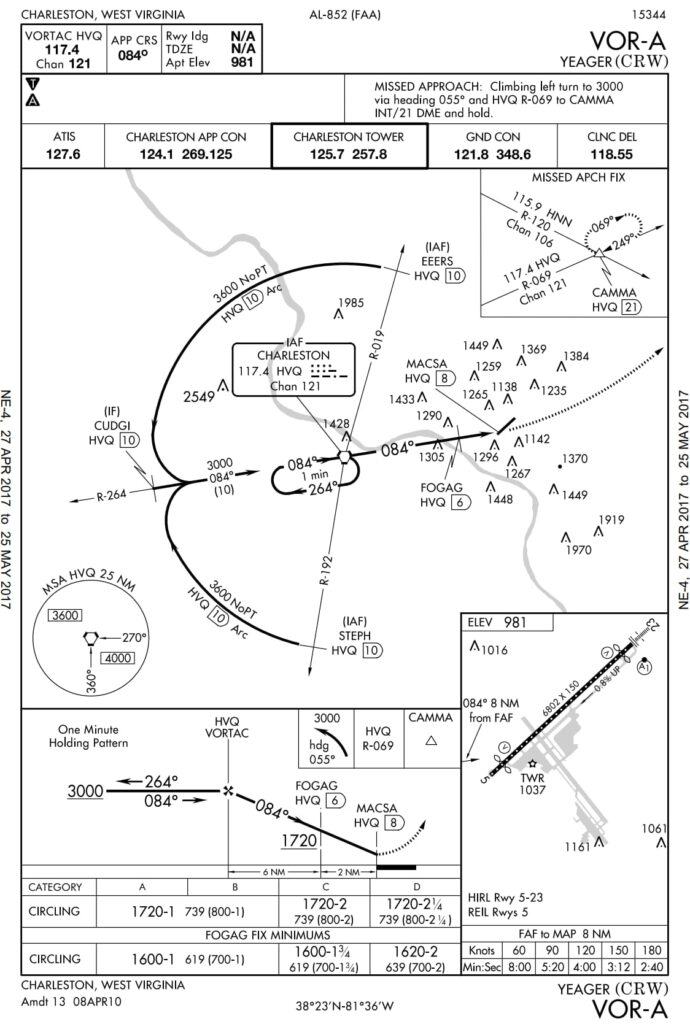

But Anh asked for the VOR-A circling approach instead. Why? Maybe they were used to it. Maybe it was routine. But it was a bad choice.

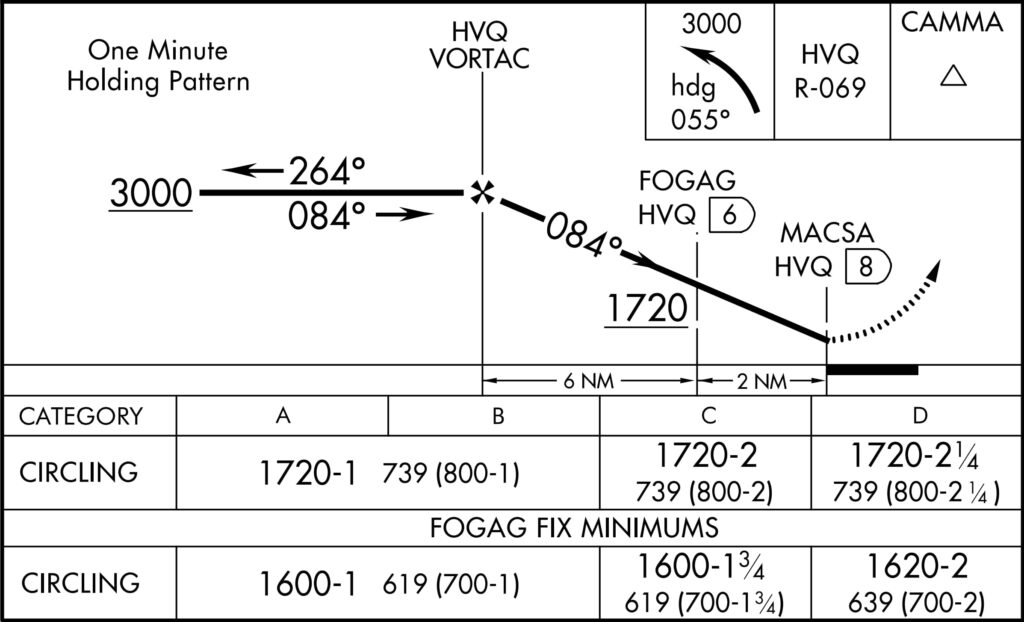

The VOR-A requires maneuvering to align with the runway. Its minimum descent altitude is 1,600 feet—too high to guarantee visual contact with the runway if the cloud ceiling is at 500 feet.

ACC’s own SOP said: use circling approaches only when a straight-in isn’t available. They’d forgotten. Or they’d drifted. Either way, the trap was set.

The Final Turn

At 6:47 a.m., radar showed the aircraft descending through 2,200 feet, well below where they should’ve been. The tower issued a low-altitude alert.

Anh responded: “We’re getting down to 1,600.”

But they weren’t even close enough to the runway yet.

They kept descending. The rate peaked at 2,500 feet per minute. The aircraft leveled off briefly, then dropped again. A half mile from the runway, at 600 feet AGL, the Captain yanked the aircraft into a 42-degree left bank to try and line up with the pavement. It was too much, too late.

The left wingtip hit first. Then the main gear. Then the propeller. The wing tore off. The aircraft skidded through a field and down a wooded hill. Both pilots died on impact.

It Wasn’t the First Time

The NTSB pulled radar data and discovered something chilling: this same Captain had flown the same circling approach into Charleston three times in the previous four months.

And every time, he descended below minimums in instrument conditions.

It had become normal for him. He was used to getting away with it. This time, he didn’t.

What We Can Learn

This wasn’t just a mistake. It was a system failure—of oversight, of safety culture, of leadership.

Anh was doing her best in a broken structure. She should have had someone to turn to. She should have had backup. She should have had options.

Instead, she was left flying solo—sometimes literally.

This tragedy reminds us:

- Complacency kills.

- Circling approaches are not routine—they’re risky.

- Permanent crew pairings demand oversight.

- New pilots need real support—not just a phone number.

- When procedures become optional, safety becomes fragile.

Anh’s story is heartbreaking not just because of how it ended, but because of how avoidable it was. She was talented, motivated, and cautious. She deserved better from the people who hired her. So did every pilot who might walk into the same situation tomorrow.

Let’s make sure no one else has to.

3 Comments

Read all the text messages. Must have helped the investigation to get an idea what her professional life was like. I’m a bit horrified the plane had no autopilot, captain was asleep and she was texting *a lot*. But she shouldn’t have had to. It’s so sad. She was young, keen and could have got a job with British Airways over here. Instead she ends up being killed working for some Mickey Mouse airline. I realise I was mistaken commenting on YouTube when I said the Captain’s past should have been investigated. I’d forgotten that it wouldn’t have revealed his failed check rides. I hope that loophole is now closed.

Hey, Hoover,

Great presentation as usual (except for the AI images, of course).

However, given the insane speed and angle of decent when the plan impacted the runway, I think that in this case, it would have been super-helpful to show the entire video. I agree that most times, there’s no need to show the final impact, but this one is off the charts.

Thanks for all your hard work! 🙂

poor girl may she rest in peace