Setup and Crew

This one took place on a hot June afternoon over South Texas. The airplane was a 1964 Cessna 182G—solid, simple, and usually forgiving. The pilot, 32 years old, held a private pilot certificate with single-engine land privileges and no instrument rating. Her logbook told a story of rapid time-building in one airplane: about 212 total hours, 208 of them in the 182. Of those, roughly 80 hours were as PIC. It was a VFR hop under Part 91 with one passenger on board. The plan was straightforward: depart New Braunfels (BAZ) and head south for a full-stop landing at Kenedy Regional (2R9). The aircraft never made it to the runway.

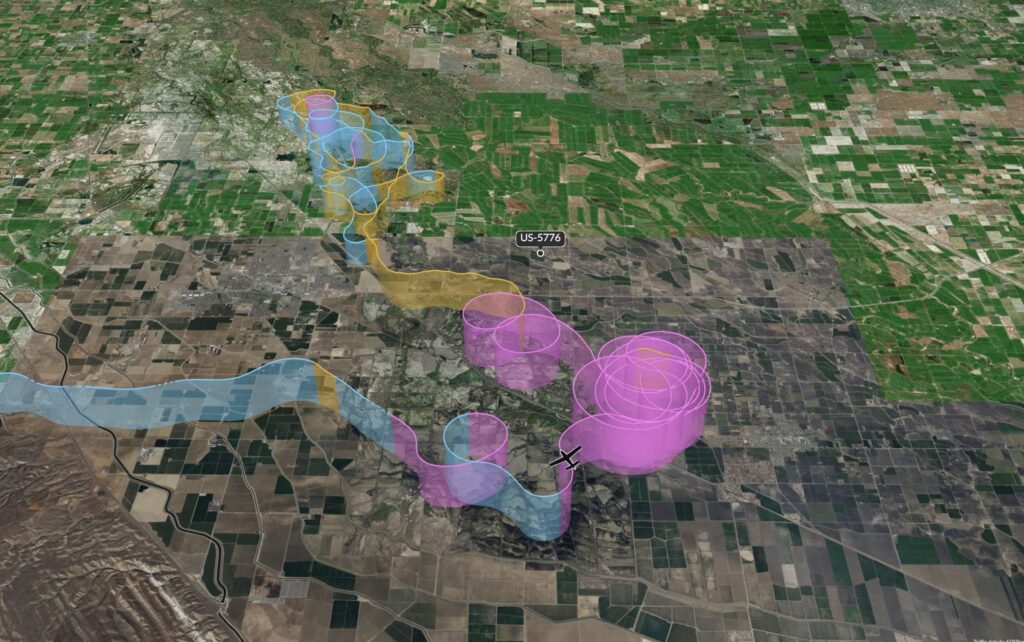

The Flight

ADS-B data showed an ordinary profile out of New Braunfels around 1452 local, a brief climb to about 6,300 feet MSL, and then a descent that settled near 5,600 feet before the pilot started down toward Kenedy roughly 23 miles out. Nothing unusual jumped off the trace. Speeds and descent rates sat comfortably in the Cessna’s wheelhouse. By about 1516 the pilot had nudged the track to line up with the extended centerline for runway 16 at Kenedy, a 3,218 by 60-foot strip of asphalt at 289 feet MSL. The weather was pure VMC—10 miles of visibility, clear skies, and winds from 130° at 19 knots. Hot, too: 37°C on the field. The airplane continued inbound, wings level, looking like a routine straight-in.

Final Approach

This is where the narrative changed. About three seconds before the final ADS-B hit, the trace showed the Cessna easing into a left bank that grew to roughly 30 degrees. Another pilot inbound to Kenedy heard the straight-in call on CTAF and initially saw the 182 steady on the extended final. Moments later, he caught a glimpse of the airplane about 30 feet above the ground, descending in what looked like a spin. A nearby surveillance camera captured the last instant: steep nose-down, left-wing-low—classic loss of control right at the bottom of the envelope. The impact point sat about 0.8 miles north of the threshold, roughly an eighth of a mile from that last ADS-B return.

Impact and Wreckage

The wreckage pattern didn’t tell a story of in-flight breakup. All the major pieces were there, the damage was consistent with a hard, near-vertical arrival, and post-recovery engine checks didn’t reveal anything that would scream power loss. Flight control continuity broke where you’d expect from impact forces. No soot, no fire. Just a Cessna driven into the ground along a fence line, the cabin crushed. Investigators did, however, find something odd in the flap system: the left flap extension cable’s swaged end was separated and the cable had come off its pulley. The end fitting itself was never recovered, which meant they couldn’t say whether it failed before impact or as a result of it. Witness marks on the pulley suggested contact by the cable’s end washer, but again, whether those marks were made in normal service or during the accident sequence couldn’t be resolved. The actuator position lined up with 40° of flap extension.

Aircraft and Maintenance

N2118R was the definition of a well-used but serviceable 182: around 5,604 hours on the airframe, Continental O-470-R up front, and a normal category airworthiness certificate. The last annual had been completed about ten months prior, and there were roughly 130 hours since that inspection. On this model, the flap system is electric. The actuator lives in the right wing and drives the right flap directly; the left flap rides along via an extension cable and a separate retraction cable. If the extension cable lets go in flight, the left flap can trail up from whatever position you selected while the right flap stays put, setting up an asymmetric condition. If the retraction cable breaks, the opposite limitation applies.

Weather and Environment

Let’s talk about the environment the pilot was working with on short final. Winds reported at 2R9 were 130° at 19 knots—nearly down the runway for a landing on 16, but with enough crosswind component to keep you honest if you wandered left or right of centerline. Density altitude? With 37°C on the ramp and 29.67 inches on the altimeter, it was a hot day by any measure. None of that should have been beyond a 182’s capability, and certainly not at the speeds the ADS-B later estimated. For the last 90 seconds of recorded data, calibrated airspeed hovered near 90 knots and came back to about 80 knots at the end. Vertical speed ranged between level and roughly -830 fpm. On paper, still a safe margin above the 182G’s published stall speeds: 56 knots clean, 48 knots with 40° flaps in level flight—and about 60 and 51 knots, respectively, in a 30° bank.

Medical Factors

The pilot flew under a third-class medical via a special issuance for mild depression and anxiety, managed with sertraline since early 2020 and well-documented in her file. Postmortem tests showed sertraline and its metabolite at levels consistent with therapeutic use. The autopsy also found a 75% narrowing in a segment of the left anterior descending coronary artery—significant coronary artery disease that raises the risk of a sudden cardiac event. The tricky part is that such events often leave no forensic fingerprint if they happen right before death. In this case, the NTSB couldn’t determine whether a medical event occurred, and they considered it unlikely that her treated depression, anxiety, or sertraline played a role.

What Likely Happened

The Board stopped short of claiming a precise mechanism. Their probable cause named a loss of control on final for reasons that couldn’t be pinned down. But the evidence did allow for one plausible scenario worth discussing for training: an asymmetric flap condition at low altitude. If the left extension cable had separated before impact, aerodynamic loads could have nudged the left flap up toward retracted while the right flap stayed extended. That would push the airplane into a left-rolling tendency. At 80–90 knots on short final, a slow, uncommanded roll could be subtle at first—just enough to invite correction with aileron. Add a 19-knot wind and a narrow runway to focus your eyes down the centerline, and it’s easy to imagine a pilot supplementing that roll correction with rudder to “square up” the picture. The ingredients for a classic cross-controlled, stall-spin entry can come together fast, especially if the airplane is slowing and the bank angle creeps up. That’s a hypothetical, not a conclusion, but it fits both the ADS-B’s gentle left bank progression and the witness video of a left-wing-low, steep, nose-down impact.

Human Factors

Experience cuts both ways. This pilot had a lot of time in type—208 hours in the 182 is meaningful—but relatively modest PIC time overall and no instrument rating. A straight-in to a small, quiet airport on a clear day can feel routine, almost benign. Yet that’s exactly where subtle abnormalities can hide. The surprise factor is real: an unexpected wing drop close to the ground, a little yaw you can’t quite iron out, or a sensation that the airplane suddenly isn’t responding the way it always does. The brain’s first response is often to fix the picture, not diagnose the system. That bias toward “make it look right now” is powerful in the flare and on short final, and it can lead to crossed controls or a deepening bank as airspeed decays.

Safety Takeaways

A few lessons stood out to me reading this one:

- Guard the energy state on final. The ADS-B suggests the 182 was flown in the 80–90-knot bracket late in the approach—reasonable numbers. But airspeed is perishable, especially when you’re trimming, adding/deleting flaps, or fighting a little roll. If the picture starts to go weird, the first tool is power. Arrest the sink and buy time.

- Treat uncommanded roll as an immediate go-around cue. Whether it’s a gust, a bird strike, a mis-set trim, or an asymmetric flap, an airplane that wants to roll on short final is telling you the approach is no longer stabilized. Add power, level the wings, and sort it out up high.

- Respect flap asymmetry as a real threat. The 182’s cable-and-pulley system is robust, but any split-flap scenario can be disorienting. If you suspect it—yoke forces feel wrong, roll input isn’t producing the usual response—stop changing configuration, keep the speed up, and go around. Fly a generous pattern, use partial flaps, and land long on a big runway if you can.

- Don’t let “routine” lull you. A straight-in VFR arrival can feel like a checklist of muscle memory. Keep a little bandwidth in reserve for the unexpected: a gust, a control anomaly, or something that just doesn’t match your mental model.

- Medical risk belongs in our self-brief. The coronary disease finding couldn’t be tied to this accident, but it’s a reminder that “I feel fine” isn’t the same as “I’m low-risk today.” Know your body, know your meds, and build margins accordingly.

Closing Thoughts

N2118R’s story was short and ordinary until the last minute—then it became a stark reminder that the bottom of the pattern is no place to troubleshoot. The Board couldn’t say for sure whether a flap cable failed in the air or during the crash. They could say the airplane departed controlled flight on final and never recovered. For the rest of us, the homework is simple: when the airplane stops behaving the way it always has, add power, go around, and live to brief it on the ground.