On July 8, 2007, a routine departure from a gravel airstrip near the Northern Rockies Lodge in British Columbia turned into a disaster. A de Havilland DHC-6-100 Twin Otter, operated by Liard Air Limited, failed to clear obstacles after takeoff, striking a telephone pole and crashing into a rocky embankment. The fiery aftermath left one passenger fatally burned, one pilot with severe burns, another pilot with serious impact injuries, and two passengers with minor injuries.

This accident wasn’t caused by weather, mechanical failure, or bird strikes. Instead, it was a series of poor decisions, miscalculations, and overconfidence that sealed the aircraft’s fate.

A Charter Operation in the Canadian Wilderness

Liard Air Limited was a small, privately owned charter company that operated out of Muncho Lake, British Columbia. Their primary business involved flying tourists to remote fishing, hunting, and sightseeing locations. The company had a fleet of four aircraft, including the Twin Otter, which was mainly used to transport guests from the lodge to major airports like Vancouver and Edmonton.

The company had access to two gravel airstrips in the area:

- The Muncho Airstrip – Located 10 km south of the lodge, this airstrip was 1,700 feet long and the preferred choice for heavy takeoffs with passengers.

- The Lodge Airstrip – A much shorter, 950-foot gravel strip, located right across from the lodge, which was mainly used for parking the Twin Otter overnight.

Normally, passengers and cargo were flown or driven down to the Muncho Airstrip before takeoff, but on the day of the accident, the pilots decided to take off directly from the lodge airstrip—a decision that would prove fatal.

The Lodge Airstrip: A High-Risk Takeoff Zone

Taking off from the lodge airstrip was inherently dangerous for the Twin Otter:

- It was only 950 feet long, significantly shorter than what a fully loaded Twin Otter needed.

- The runway had a 2° uphill slope, increasing the takeoff distance required.

- The Alaska Highway crossed 100 feet past the departure end, meaning little room for error.

- A telephone cable was strung 47 feet above the highway, creating an immediate obstacle in the flight path.

- The airstrip had no windsock, meaning pilots had to guess the wind direction.

Despite these risks, Liard Air had an unwritten policy that all Twin Otter departures from the lodge airstrip would be done with minimum fuel and no passengers—a policy that would be completely ignored on this flight.

The Crew: Experienced but Unfamiliar

The Captain

- Airline Transport Pilot License (ATPL)

- 22,000 hours total flight time

- 6,000 hours in Twin Otters

- Hired as Chief Pilot in June 2007, just one month before the crash

- Only flown out of the lodge airstrip three times, once as captain

The captain was highly experienced, but new to the company. His Twin Otter experience was primarily with the DHC-6-300 model, which had better short-field performance than the DHC-6-100 they were flying that day.

The First Officer

- ATPL

- 10,800 hours total flight time

- 105 hours in the Twin Otter, all on this aircraft

- Mostly flown larger aircraft, with little bush-flying experience

The first officer was also new to Liard Air and, just like the captain, had only flown out of the lodge airstrip three times.

While both pilots were experienced, neither had practiced maximum performance short takeoffs (MPS) in the Twin Otter—a critical skill for operations from a strip this short.

The Plan

Originally, the plan was to use a Cessna 172 to transport a guest to Vancouver. However, concerns about potential bad weather en route led to a switch to the Twin Otter. The decision seemed practical, but it introduced new challenges, especially with weight and takeoff performance.

The aircraft was filled with fuel, and more passengers were added, pushing the takeoff weight to the upper limit. Unfortunately, no performance calculations were done to verify if the heavily loaded Twin Otter could safely depart from the short, sloping gravel airstrip.

Weight and Balance Issues

The aircraft was filled with fuel (estimated 2,600 lbs) and loaded with three passengers. The calculated weight was 9,956 lbs, well within the maximum limit of 11,579 lbs. However, this didn’t take into account the takeoff performance limitations for a short, uphill, gravel runway.

- The actual takeoff weight was later estimated to be slightly over 10,100 lbs due to additional unaccounted gear.

- The aircraft’s center of gravity was within limits but further forward than calculated, due to incorrect starting values used in the company’s weight and balance tool.

The Critical Mistakes in Takeoff Execution

- Brakes were released before reaching takeoff power, reducing acceleration.

- The aircraft did not use the full available runway—about 86 feet of usable strip was left behind.

- At halfway down the strip, the captain applied full aft elevator, causing the aircraft to momentarily lift off before settling back down.

- As the end of the airstrip approached, the captain advanced power to the stops in a last-ditch effort.

- The aircraft drifted left, struggling to get airborne.

- The right outboard flap hanger clipped the ground near the highway.

- The aircraft struck a telephone pole and cable, then crashed into a rocky embankment.

The resulting post-impact fire (PIF) destroyed the aircraft.

The Aftermath and Survival Factors

The Fire That Sealed Their Fate

- The impact forces were survivable, and all five occupants escaped the wreckage.

- However, jet fuel from ruptured tanks ignited immediately, engulfing the cabin.

- The captain suffered serious burns while escaping.

- One passenger was unable to escape quickly enough but succumbed to burn injuries.

Safety Equipment Failure

- The first officer’s shoulder harness snapped on impact due to age and UV exposure.

- The harness had deteriorated well beyond manufacturer specifications, highlighting the need for regular seatbelt inspections and replacements.

What Went Wrong? The Key Findings

1. Takeoff Performance Was Not Calculated

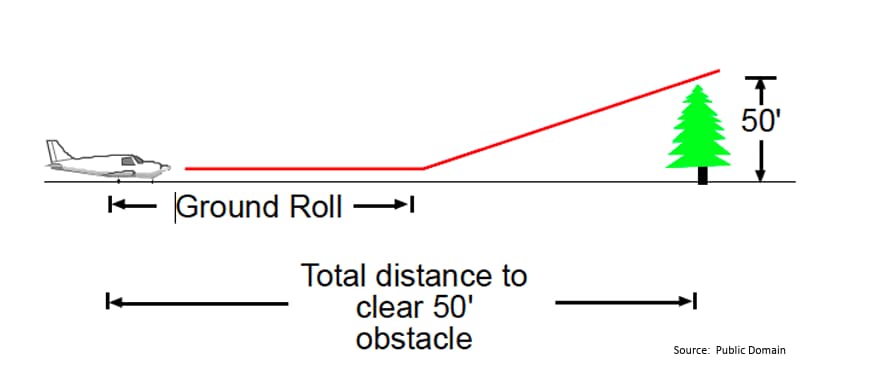

- If the pilots had done the math, they would have realized they needed at least 1,350 feet (with 10° flaps) or 1,175 feet (MPS takeoff) to clear a 50-ft obstacle.

- The available runway was only 950 feet—the takeoff was impossible from the start.

2. The Aircraft Was Too Heavy for the Conditions

- Just because an aircraft has short takeoff capabilities doesn’t mean it can take off from any short runway.

- The combination of a heavyweight aircraft, upslope, gravel surface, and a slight tailwind made taking off a dangerous gamble.

3. The Takeoff Was Poorly Executed

- Not using the full runway length made the aircraft’s performance margin even slimmer.

- Brakes were released before full power was reached, reducing acceleration.

- The pilots never discussed abort criteria and failed to abort when the First Officer mentioned the left engine wasn’t at full power

4. Organizational and Decision-Making Failures

- The captain was new to the company and unfamiliar with this airstrip’s dangers.

- The first officer prepared the aircraft but did not verify the feasibility of the takeoff.

- The company did not enforce proper pre-flight planning for short-field operations.

- The company had no standard operating procedures (SOPs) for Twin Otter short-field takeoffs.

Final Thoughts

This crash wasn’t an accident—it was entirely preventable. If the pilots had simply run the performance calculations, they would have known this takeoff wasn’t possible. Unfortunately, one passenger died as a result of human factors, operational shortcuts, and decision-making errors rather than mechanical failure.

2 Comments

I FLEW out of this lodge and always refused to use the strip. It is legal to use the road in this part of Canada…The strip was at my time there rough, and in my

decision unusable.

Thanks for sharing that insight and personal experience!