Sometimes in aviation, it’s not about one big mistake—it’s a series of small ones, stacked just right, that bring an aircraft to its knees. That was the case in Afton, Wyoming, when a newly purchased Piper PA-22-150 ended up wrecked beside the runway just moments into a flight meant to celebrate its new ownership.

The First Flight

It was a crisp May evening at Afton Municipal Airport (elevation 6,221 feet), where a 21-year-old student pilot had just acquired his new-to-him tailwheel Piper. Eager to get it in the air, he enlisted the help of a commercial pilot—someone he had met just hours before. She had more than 4,500 hours of flight experience, including 400 hours in this specific make and model. But she didn’t know he was a student pilot. And he didn’t realize that flying a new aircraft type, at high elevation, required careful coordination—especially on takeoff.

The Pilots

Commercial Pilot:

- Certificate: Commercial (single-engine land/sea, multi-engine land/sea)

- Total Time: 4,500 hours

- Time in Type: 400 hours (PA-22-150)

- Seat: Right

- Age: 33

Student Pilot (also the aircraft owner):

- Certificate: Student Pilot

- Total Time: 48 hours

- Time in Type: 0 hours

- Seat: Left

- Age: 21

Neither pilot reported any mechanical malfunctions, and both walked away without injury. The runway was dry, the weather was clear, and visibility was 10 miles.

Confusion on the Roll

During the takeoff roll on Runway 34, something felt off immediately. According to both pilots, the airplane briefly lifted off, then settled back down. Moments later, it veered right, skidded through a fence, and nosed over, crumpling the wings and wing struts. The good news: neither occupant was hurt. The bad news: the airplane suffered substantial damage—and the NTSB had some questions.

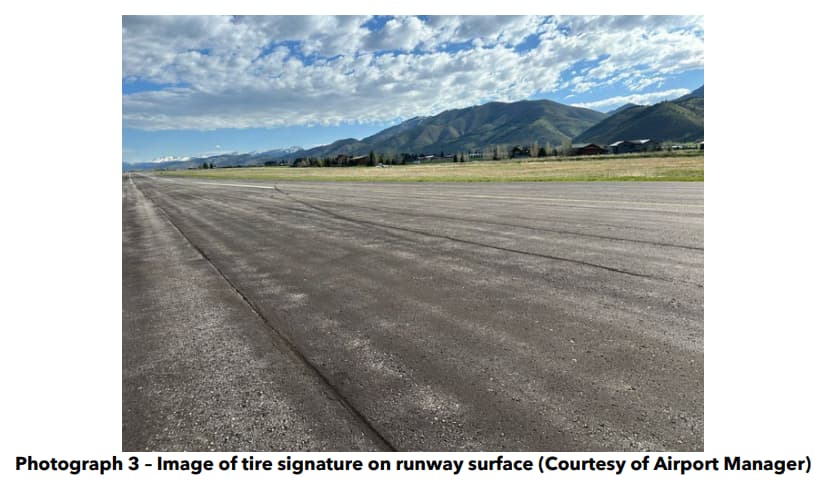

The commercial pilot said she wasn’t flying—the student pilot was. But the student insisted the commercial pilot had applied power and taken the controls. Photographs of the accident scene told their own story: tire marks and grass scarring indicated the brakes had been applied the whole way through. Critically, in this Piper, the brakes are only accessible from the left seat—where the student was sitting.

To make matters more complicated, a post-accident inspection revealed the elevator trim had been set to full nose-up. Not ideal for takeoff.

What Went Wrong

The NTSB’s analysis focused on three key breakdowns:

- Loss of directional control during takeoff.

- The student applying brakes—likely unintentionally—throughout the roll.

- Lack of positive transfer of control, meaning neither pilot clearly communicated who was flying the aircraft.

Ultimately, the commercial pilot was held responsible for failing to maintain control. But the report also cited the student’s brake usage and poor cockpit communication as contributing factors.

A Familiar Mistake in a Classic Plane

The Piper PA-22 Tri-Pacer, like many tailwheel aircraft, can be a handful on the ground. Directional control on takeoff and landing is a skill that takes time to master, especially at high elevation airports where density altitude works against you.

In this case, the aircraft itself was airworthy and freshly inspected, but the human element failed. Despite her experience, the commercial pilot didn’t ensure a clear briefing or verify the skill level of the pilot next to her. The student, excited but underprepared, likely acted out of nervousness—and may have frozen on the brakes without realizing the consequence.

Lessons from Afton

This accident highlights a few timeless truths in aviation:

- Know your crew. Even a short hop demands clear communication and a shared understanding of roles.

- Transfer of controls isn’t optional. Pilots should use clear, verbal cues (“I have the controls”)—especially during takeoff and landing.

- New aircraft, new habits. Familiarization flights should be slow, deliberate, and with experienced, type-current instructors who know what to expect.