On July 26, 2021, a Bombardier Challenger 605 (N605TR) crashed while attempting a circling approach to Truckee-Tahoe Airport (TRK) in California. The aircraft, carrying two pilots and four passengers, impacted terrain short of the runway, killing all onboard.

A Flight That Started Smoothly

The Challenger 605 departed Coeur d’Alene, Idaho (COE), around 11:45 AM, bound for Truckee-Tahoe under Part 91 (general aviation). The two pilots—both experienced, but flying together for the first time—planned to land on Runway 11, Truckee’s longer and safer runway.

Truckee is a challenging airport, located at 5,900 feet elevation with frequent mountainous turbulence, high density altitude, and tricky approaches. On the day of the crash, heavy smoke from nearby wildfires had reduced visibility, making the approach even more difficult.

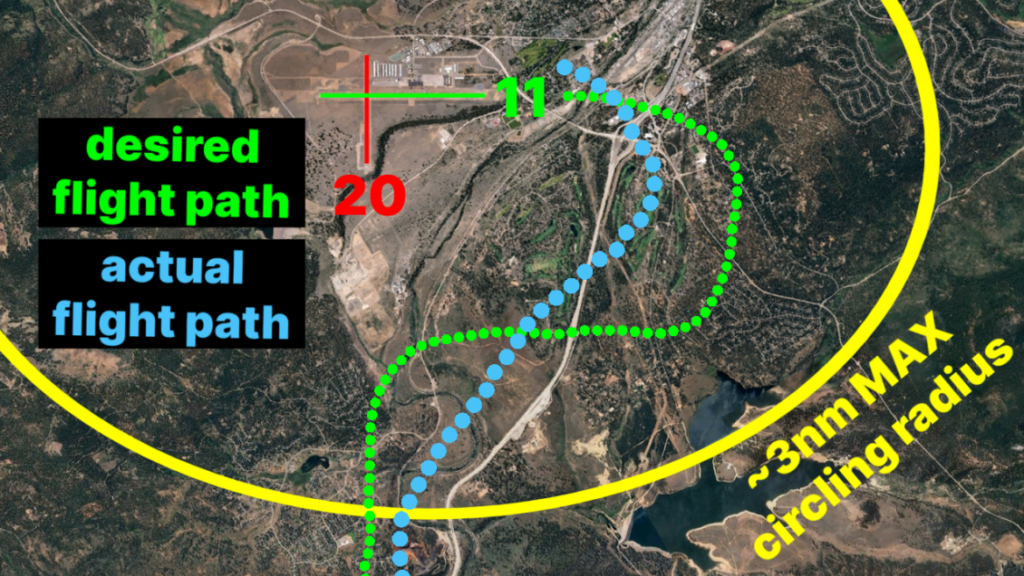

As the jet descended toward Truckee, ATC cleared the flight for an RNAV approach to Runway 20, the shorter of the two runways. The pilots immediately recognized that Runway 20 was too short for their landing weight. Instead of requesting a straight-in approach to Runway 11, the captain made the risky decision to circle-to-land—a complex maneuver that requires tight, low-altitude turns in close proximity to obstacles.

At this point, they should have briefed the new approach. However, they did not—an omission that would later prove critical.

Mismanagement of the Approach

Upon reaching Truckee’s airspace, the pilots entered a hold, waiting for their approach clearance. But the captain was slow to react, forcing the first officer (FO) to take over and initiate the turn into the hold himself.

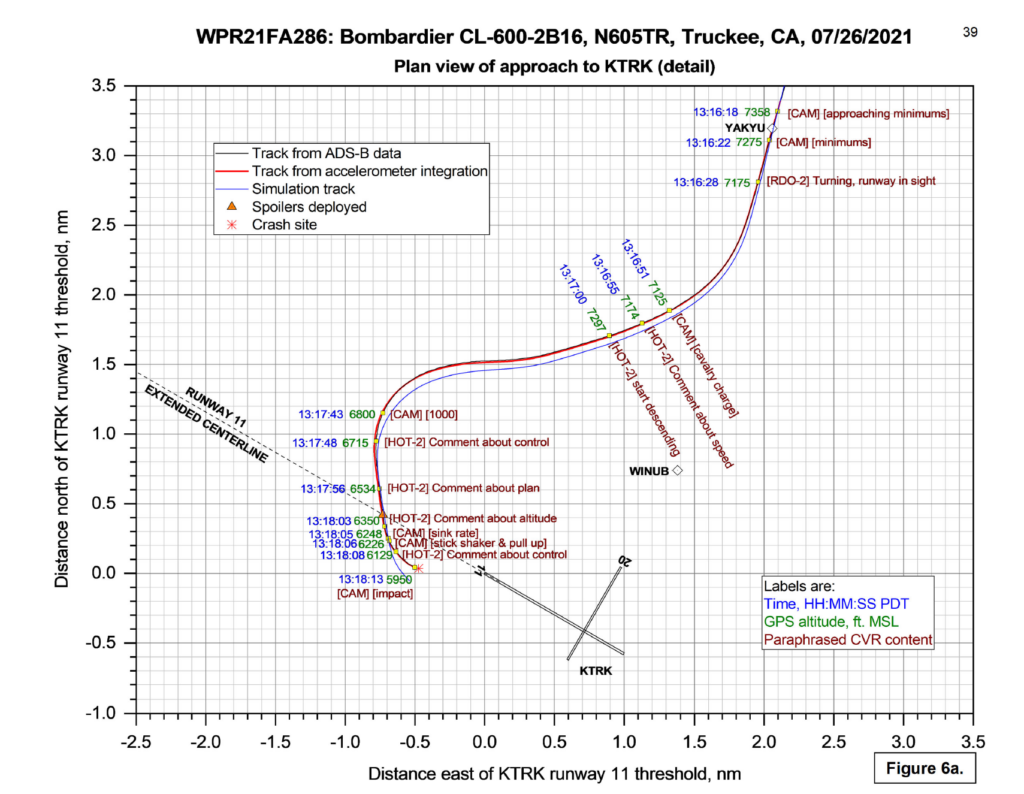

Once cleared for approach, they were still too high and too fast, flying at 252 knots—well above the maximum approach speed for their category. The FO suggested making a 360-degree turn to bleed off speed, but the captain refused.

Approaching the airport, the FO spotted the runway first and had to repeatedly point it out to the captain, likely due to poor visibility from smoke.

At this point, their approach was completely unstable:

✅ Too fast – 160 knots (Vref was 118 knots).

✅ Too high – Needed a steeper descent.

✅ Too tight of a turn to final – Making alignment difficult.

A go-around was the safest option. But neither pilot called for it.

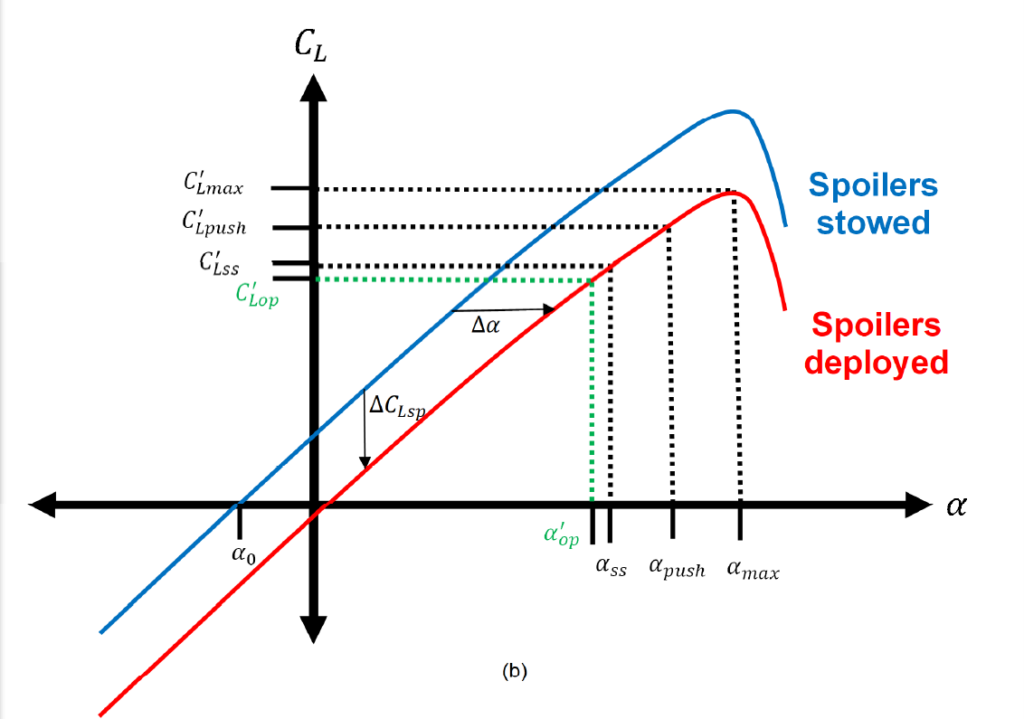

Instead, as they overshot the centerline, one of the pilots fully deployed the flight spoilers (speedbrakes), which dramatically increased the stall risk.

A Desperate Struggle for Control

With the aircraft still misaligned and losing lift, the FO repeatedly asked for control, saying:

💬 “Let me have the airplane.”

The captain did not acknowledge. Instead, both pilots fought for control, causing confusion at a critical moment. Seconds later, the stall warning stick shaker engaged, and then the stick pusher activated, forcing the nose down in an attempt to recover from the stall. The FO again begged for control, but there was no positive transfer between pilots—one of the most fundamental CRM principles.

The aircraft entered a rapid left roll, exceeded 146° of bank, and plummeted to the ground, impacting just short of the runway. A fireball erupted, consuming most of the wreckage.

Why Did This Happen?

The National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) identified several major contributing factors:

1. Poor Crew Resource Management (CRM)

- The captain ignored the FO’s concerns about speed and suggested corrections.

- The FO did not assertively demand a go-around when it was clearly needed.

- In the final moments, both pilots struggled for control, but no clear transfer of authority occurred.

2. A Botched Circling Approach

- They failed to brief the new approach, leading to confusion.

- The captain did not establish a proper downwind leg, forcing an excessively tight turn to final.

- The high speed and late corrections left no margin for error.

3. Self-Induced Pressure to Land

- There was no external pressure to land immediately (they had fuel and time).

- Yet, they ignored clear signs of an unstabilized approach and continued instead of going around.

4. The Flight Spoilers Worsened the Stall

- Having the spoilers deployed while in a steep, slow turn dramatically reduced the stall margin.

- This action likely caused the left wing to stall asymmetrically, leading to the fatal roll.

Key Takeaways for Pilots

✈️ 1. If the Approach is Unstable, Go Around!

- If you’re too high, fast, or misaligned, abort the landing.

- The Challenger’s flight manual and company guidelines explicitly required a go-around at this stage.

✈️ 2. Circling Approaches Are Dangerous

- They require low, tight turns near obstacles—a known risk for loss-of-control accidents.

- If conditions aren’t perfect, opt for a straight-in approach or divert.

✈️ 3. Communicate Clearly & Assertively

- The FO should have demanded a go-around when the approach became unstabilized.

- The captain should have clearly transferred control instead of leaving it ambiguous.

Final Thoughts

This tragic accident was preventable. The flight crew ignored multiple warning signs—excessive speed, poor alignment, miscommunication, and a rushed approach—all of which should have triggered a go-around.

This case serves as a sobering reminder that unstabilized approaches, poor CRM, and last-second corrections often end in disaster.

For pilots, the message is clear: If it doesn’t look right, don’t force the landing. Go around.